Marije Miedema*

This blog post is based on the master’s thesis completed at the Research Master Arts, Media and Literary Studies, at the University of Groningen. It highlights one specific part of the methodology (reflective video diaries). To read the full thesis, click here, or reach out by e-mail.

Toothbrushing is embedded in our daily routines, so much so that we often do not pay particular attention to it, even though oral health is an integral part of our well-being since almost everything that enters the body passes through the mouth. It is a mundane task that we generally do not consciously reflect upon daily. To prevent healthcare issues, we improve our dental hygiene by brushing, picking and flossing our teeth daily (or at least, this is what we tell our dentist). Oral health is a part of and is shaped by complex ethical, social, and technological infrastructures (Jones & Gibson, 2023; Holden, 2020). This makes oral health and dental hygiene a compelling but still underrepresented anthropological and sociological research topic (Exley, 2009; Kleinberger et al., 2014), with some notable exceptions that explicitly mention the benefits of qualitative methodologies like ethnography (Vasthare et al., 2024; Jones & Gibson, 2023; Carter et al., 2013; Horton & Barker, 2010).

Triggered by the potentialities of this mundane everyday task, I decided to engage with oral hygiene ethnographically, more specifically, toothbrushing and the introduction of smart toothbrushes. That is how I got introduced to the Oral-B iO9 Toothbrush (see Figure 1) which informed the following research question: How does a smart toothbrush perform smartness during engagement in everyday life? This gave rise to the following three sub-questions: (1) To what extent is smartness inscribed into the smart toothbrush? (2) In what ways is the smart toothbrush capable of behaviour change? (3) How is smartness situated in the interaction between the user and the toothbrush? Though I will briefly touch upon these questions through two examples of the findings, this blog post mainly focuses on the meta-question underlying this research project: What does it mean to do an ethnography of oral health?

Methodologies of the mouth

During the fall of 2020, I carried out ethnographic research involving smart toothbrushes. Due to the lack of previous studies on toothbrushing in situ, I began with an initial autoethnographic research phase that involved field notes and video diaries to inform the ethnographic research with two participants. They were similar in terms of age (30), demographics (Dutch), and socioeconomic status (middle class) but different in their experience with oral hygiene. One participant, referred to as ‘The Novice’ did not have any previous experience with smart technologies or professional engagement with oral health, while the other, referred to as ‘The Expert’ was a dentist working in two dental clinics with an interest in smart technology. At the start of the research phase, I conducted a semi-structured life-world interview in which we discussed their current oral hygiene and experience with smart technologies. This was followed by a 4-week period where the participants recorded reflective video diaries; for the first two weeks, they used their own toothbrushes and for the following two weeks, the Oral-B iO9, see Figure 2. They were asked to create at least two video diaries per week and were encouraged to express their thoughts before, during, or after toothbrushing out loud. After this period, I conducted one more interview to reflect on their experience with the smart toothbrush and their participation in the research project, which allowed me to validate my interpretations of the data.

When two minutes is not enough

When doing ethnographic research, the researcher meticulously observes the lived experiences regarding the object of research. Ideally, the ethnographer fully immerses themselves in the daily life of their participants for extended periods, also known as participant observation. However, methodological challenges arise when the research topic is a smart toothbrush. The World Health Organization recommends that you brush your teeth with fluoride-containing toothpaste at least twice a day, for two minutes each time. Doing participant observations over an extended period would thus be far from ideal as waiting at the participant’s home for them to brush their teeth would be burdensome for both the participant and the researcher. Furthermore, ethical issues arise because the home is not a controlled environment, but a place of security, activity, relationships, and identity (Gram-Hanssen & Darby, 2018). Conducting interviews alone would also be inadequate, as my participants tended to forget to mention toothbrushing when describing their daily routines, despite being aware of the topic of the interview. Instead, I introduced reflective video diaries. Next to pointing the camera at their face while brushing their teeth, showing the practice, the participants reflected on their toothbrushing experience directly after the toothbrushing. Sometimes they had to think about what to say, other times they had their reflections ready. This reflexive practice has been instrumental in showing how offline and online spaces are merely conceptually distinct, and instead are always entangled (Kaufmann & Palmberger, 2022). With this reflexive component, the video diaries proved to be very valuable, going beyond the creation of audio-visual data and serving as a positive disruption tool in the mundane nature of this everyday task.

Let me explain this by delving further into the methodology. A critical aspect of qualitative data analysis involves comparing findings to identify differences and similarities. However, since this data was not available for toothbrushing, I incorporated comparison in the research design, which I refer to as the “qualitative experiment”. During the initial two weeks, the two research participants used their own electric toothbrushes, followed by an ‘intervention’ in the form of the Oral-B iO9 toothbrush, which they used for the subsequent two weeks. This intervention allowed for comparison within the research project. It prevented the simultaneous introduction of both the research method and an unfamiliar research object, thereby avoiding confusion for the participants, which could impact their reflections. Prior to the intervention, the video diaries had already highlighted the daily nature of the routine by pointing a camera at it. The Expert describes how toothbrushing is typically part of multi-tasking: “Every time I have to film myself, I’m mainly busy with just brushing my teeth while normally I would do a bit of multi-tasking. I wanted to bring a coat hanger downstairs, but now this was not possible.” (Video diary, week 2). The reflective video diaries then shift the focus from the artifact to the process (Pink et al., 2017).

Brushing to score or to clean?

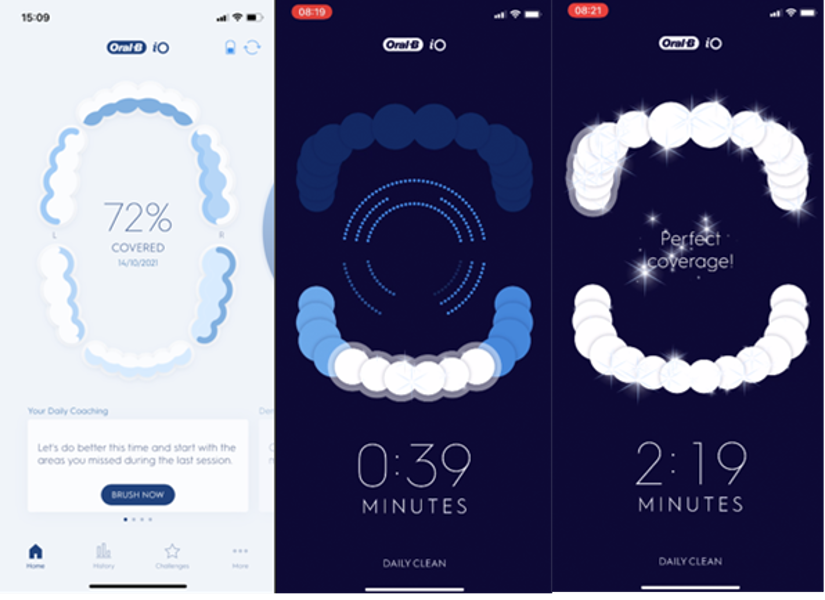

Where the first two weeks of the reflective video diaries highlighted the everydayness of their normal brushing routines, the next two weeks showed how the Oral-B iO9 smart toothbrush affected this routine toothbrushing behaviour. The smart toothbrush gives direct feedback through a smart pressure sensor that lights up green (good), blue (too soft), or red (too hard), and the handle has a built-in timer. What makes this toothbrush smart is that it comes with a smartphone application. This app tracks brushing sessions in real-time, shows the history of previous sessions, and offers challenges and rewards. In the reflective video diaries, the participants discussed the impact of these features on their brushing habits. Specifically, when the toothbrush works and fails:

If I brush at the top left, it registers, for example, the bottom right and then it says that that section is done while I haven’t been there at all. So that strikes me and that has happened quite often and somehow that irritates me. I mean, fucking hell, I try to do my best, to show that I brush well, to actually get that reward. That compliment that you brushed well; you want to get to the 100 percent. And then that doesn’t work, and because of that I am brushing for almost three minutes sometimes, while I feel like I am already finished after two minutes. That is something that annoys me. So not feeling very confident yet – I mean there is confidence, but I sometimes think this is not quite right. (The Novice, video diary 6)

In this quote from ‘The Novice,’ we see an emotional response not only directed at the failing technology but also concerning the future effects on the total brush score. The Novice wants to achieve a 100 percent score, but issues with the connection between the app and the toothbrush prevent him from reaching it. Even though the participants know the smart guide is displaying incorrect data, they still adjust their brushing behaviour to achieve the perfect score and, ultimately, the rewards. The Expert also confirms this: “I sometimes notice that it registers on the wrong side while I’m brushing on the other side, so you go and brush on the other side for a few seconds just to get those points” (video diary 8, week 4).

It is unclear how the points are distributed, and which factors are considered. The perfect score is 100, but this is not equal to 100 percent coverage. It is possible to get a 100 percent score with a little bit of overpressure, but never when brushing for less than two minutes. Oral-B does not disclose what is needed to get a perfect score. However, it does share the data insights of the different categories that can be used to improve the score average, see Figure 4. By hiding formalized rules and instead sharing statistics and scores, the company aligns with the black boxing practices in gamified health tracking (Lupton, 2016). The application’s algorithms also take over the task of the user to interpret and keep up with the set of rules. By introducing elements of scores, awards, and hidden rules into a non-play space like toothbrushing, this everyday task is gamified.

Reflective video diaries as a disruptive force

When conducting digital ethnography, it is important to seamlessly transition between offline and online spaces using our research methods (Kaufmann & Palmberger, 2020). One space where the digital and the material are increasingly coming together is the home. With almost every object in our homes capable of evolving into smart devices, we need to use research methods that have minimal impact on our daily routines to accurately describe and subsequently analyze them (Crabtree & Tolmie, 2016). Researching toothbrushing presents a unique challenge and opportunity due to their seamless integration into our everyday routines. Using reflective video diaries provides a non-intrusive yet intimate approach to studying toothbrushing in situ. These diaries served as both a method and a disruptive force, shedding light on the often-overlooked behaviours and thought processes associated with our daily oral hygiene practices. They offer novel insights into the dynamic interplay between the user, the smart toothbrush, and the surrounding environment. These reflective diaries also hold potential for studying other objects in the home, and I encourage experimenting with the method together with the participants to refine it further.

References

- Carter, S., Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2013). The domestication of an everyday health technology: A case study of electric toothbrushes. Social Theory and Health, 11, 344–367. https://doi.org/10.1057/sth.2013.15

- Crabtree, A., & Tolmie, P. (2016). A day in the life of things in the home. Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, ACM, pp. 1738–50. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2818048.2819954

- Exley, C. (2009). Bridging a gap: The (lack of a) sociology of oral health and healthcare. Sociology of Health and Illness, 31(7), 1093–1108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01173.x

- Gram-Hanssen, K., & Darby, S. J. (2018). “Home is where the smart is”? Evaluating smart home research and approaches against the concept of home. Energy Research and Social Science, 37(March 2017), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.037

- Holden, A. C. L. (2020). Consumed by prestige: The mouth, consumerism and the dental profession. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 23(2), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-019-09924-4

- Horton, S., & Barker, J. C. (2010). Stigmatized biologies: Examining the cumulative effects of oral health disparities for Mexican American farmworker children. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 24(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01097.x

- Jones, C. L., & Gibson, B. J. (2022). Cultures of oral health: Discourses, practices, and theory. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003047674

- Kaufmann, K., & Palmberger, M. (2022). Doing research at online and offline intersections: Bringing together digital and mobile methodologies. Media and Communication, 10(3), 219–24. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i3.6227

- Kleinberger, J. A., & Strickhouser, S. M. (2014). Missing teeth: Reviewing the sociology of oral health and healthcare. Sociology Compass, 8(11), 1296–1314. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12209

- Lupton, D. (2016). The quantified self : A sociology of self-tracking. Polity Press,

- Oral-B UK (Director). (2020, August 24). Oral-B iO – Series 9 Electric Toothbrush [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJx3HsZyFMg&t=4s

- Pink, S., Sumartojo, S., Lupton, D., & Heyes LaBond, C. (2017). Empathetic technologies: Digital materiality and video ethnography. Visual Studies, 32(1), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2017.1396192

- Vasthare, R., Lim Y R, A., Bagga, A., Nayak, P. P., Bhat, B., & S, S. (2024). The phenomenological approach in dentistry—A narrative review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 19(1), 2341450. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2024.2341450

*Marije Miedema is an interfaculty PhD candidate (STS and Media Studies) with a background in the visual arts at the University of Groningen. In collaboration with a theatre collective, and local archival institutions, she ethnographically researches the future of our personal digital heritage in a community center. From a critical data and archival studies perspective, she asks for whom do we preserve and at what (environmental) cost? Marije is also a board member of WTMC (Netherlands Graduate Research School of Science, Technology and Modern Culture) and editorial assistant for the Livable Futures book series at Amsterdam University Press.