Taylor Dube*

This blog post is a revision of a text written in collaboration with Melanie Strobl for the seminar “The Materiality and Visuality of Social Media” by Philipp Budka for the MA program “CREOLE – Cultural Differences and Transnational Processes” at the University of Vienna.

Taking a knee to take a stand

Social media connects us virtually – we upload, like, comment and share pictures and thoughts. Social media platforms can be democratizing, making previously exclusive discussions accessible (Bouvier, 2020; Rosenbaum, 2019). Despite this, social media can also be a double-edged sword, creating an environment of exclusion, an example of which is cancel culture.

Eve Ng defines cancel culture as: “the withdrawal of any kind of support […] for those who are assessed to have said or done something unacceptable or highly problematic” (2020: 623). Cancel culture frequents social and classic media (Bouvier, 2020; Romano, 2020; Jedicke, 2020) and is a polarizing concept.

In an effort to investigate how cancel culture manifests on social media, my colleague Melanie Strobl and I conducted an analysis of Instagram and Twitter posts, surrounding the cancelation of the former US National Football League (NFL) quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

Colin Kaepernick is an American athlete, who protested police brutality against people of color (POC) (Wyche, 2016), by kneeling during the American National Anthem during NFL games in 2016.

His protests addressed racism and violence which people of color experience in the United States, particularly at the hands of police. The reaction to Kaepernick’s protest was highly polarizing, with tension rising between not only football fans, but the American public. There were those who supported his right to protest, and those who viewed his kneeling as disrespectful to the US military. While former President Obama’s response to Kaepernick kneeling aimed a diplomatic balance between the right to protest and respect for the military, former President Trump stoked the fires of division by calling for NFL owners to “say ‘Get that son of a b**** off the field right now.” (Carcian, 2020). This hints at not only the level of media coverage and scrutiny Kaepernick’s protest received, but also the highly politicized nature of the conversation surrounding it.

This study investigated how social media played a role in the cancelation of Colin Kaepernick, namely the withdrawal of support, which ranged from calls for his firing to calling him unAmerican. We investigated the online manifestation of cancel culture and the impact cancelation had on Kaepernick’s career, as he played his last season in the NFL that year.

What do we know about cancel culture?

Cancel culture is not a new phenomenon, however it is understudied in academia. Meredith D. Clark refers to “blacklisting and boycotting” as cancel culture’s “analogue antecedents” (2020: 89). This sentiment is echoed by Hooks (2020: 4) who described cancel-culture as a “variant of call-out culture” and essentially differentiates the two as public shaming (call-out) vs. boycotting (canceling). Despite their slight differences, both seek to negatively impact the reputation of the wrong-doer (Hooks, 2020: 12).

Canceling finds its roots in queer communities of color (Clark, 2020) as a tool created by people of color as a “call out” and a platform for vocalizing inequality. Social media is the fertile ground for its recent bloom. Social media enables the sharing of moral capital via posts, comments, etc. (Bouvier, 2020), and as such a way to participate in cancel culture. Clark (2020) argues examinations of cancel culture must include examinations of power structures. This is particularly true in the case of Kaepernick, as a biracial man (Johnson, 2016), addressing racial inequality and police brutality; power structures are at the heart of discussion surrounding his cancelation.

Judith Rosenbaum’s (2019) study offered a suitable framework for our own analysis, analyzing tweets and Instagram posts using #TakeaKnee (trended in September 2017, related to Kaepernick’s kneeling) to elaborate on social media users’ understanding of American identity.

Typically only “celebrities, brands, and otherwise out-of-reach figures” are canceled (Clark, 2020: 89), but as Ng (2020) states, cancel culture affects far less prominent individuals. Celebrity or not, this phenomenon can, in theory, affect anyone. The requirement? Enough people agree en masse that a wrong has been done and call for retribution.

Selecting Kaepernick as a case study for cancel culture

Kaepernick’s social media presence, the extensive and prolonged media attention his case drew, and the well documented instances of positive and negative outcomes made this case ideal for analysis.

Here were our steps:

- Data collection: We collected news articles addressing Kaepernick’s protest. This provided context and a timeline for his cancelation and the eventual present day repercussions.

- Kaepernick’s Instagram: His posts were used to contextualize the events surrounding the 2016 cancelation. Two of Kaepernick’s Instagram posts which addressed the protest directly were selected for analysis.

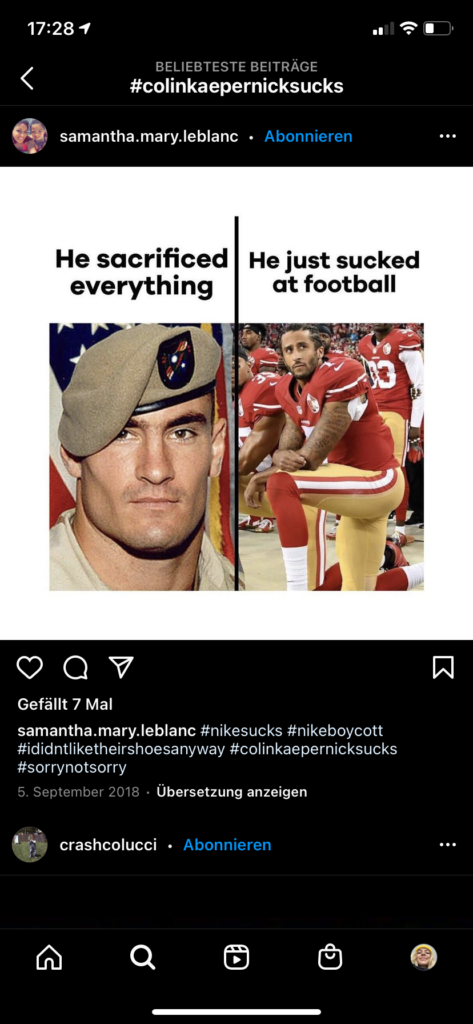

- The bulk of our posts selected for analysis were collected via #colinkaepernicksucks (Instagram), #cancelkaepernick (Twitter), and #veteransforkaepernick (Twitter/Instagram). The selected posts which used the aforementioned hashtags exemplified visual and written responses to Kaepernick’s protest, indicating either a continuation or a withdrawal of support. The keyword cancel and #veteransforkaepernick were used to collect data for the support of and opposition to Kaepernick’s cancelation, respectively.

Kaepernick’s case spanned several years and has been a global conversation. Conversation surrounding Kaepernick’s protest resurfaced in the summer of 2021 when athletes knelt at the UEFA Euro 2021 European Football Championship and an Instagram post by Kaepernick from 2016 addressing his protest was commented on as recently as April 2022. Our research utilized an interpretive content analysis, unrestricted by coding rules, allowing for flexibility to take the context more fully into account (Ahuvia, 2001). Kaepernick’s cancelation continued for years, requiring a broader context, thus provided for by an interpretive content analysis. Following the principles of interpretive content analysis, visual and textual material of the Instagram and Twitter posts were coded into categories and the results interpreted in relation to our research question.

A system of five relevant categories was developed for the textual analysis and a system of two categories for the picture analysis. Text seen on a picture was also coded in the text analysis.

Analyzing the data

Our research yielded examples of what can be considered a counter-cancel culture. Support for Kaepernick manifested online as #ImWithKaep, #TakeAKnee, #VeteransForKaepernick.

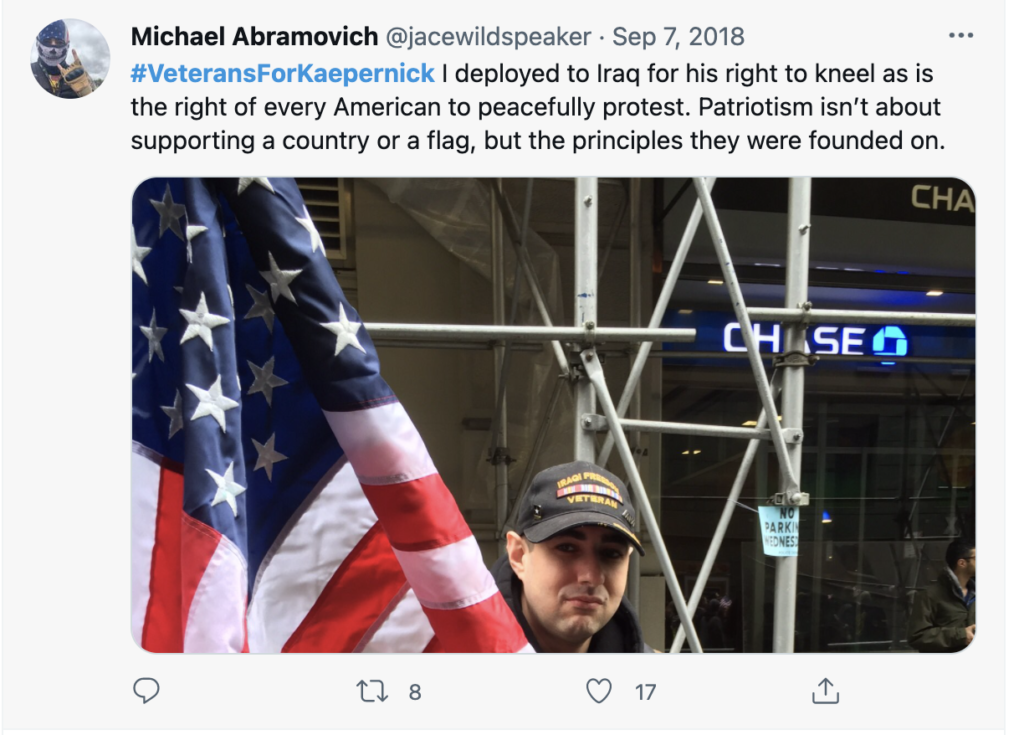

In one post, the caption states, “Its (sic) a misconception that every military member is furious at his protest when there are those that are proud.” (@nasir.premier, 2016). In the selected #veteransforkaepernick posts, all three users selected photos of themselves wearing uniform or military attire to situate themselves in a position of authority on the topic.

The photos visualizing their military service accompanied a text indicating the reason they support Kaepernick and the values guiding their service. Another post reads, “I deployed to Iraq for his right to kneel […] Patriotism isn’t about supporting a country or a flag, but the principles they were founded on.” (Abramovich, 2018). The veteran clearly expresses his values, indirectly referring to Kaepernick as patriotic. Conversely, a post with #cancelkaepernick expresses the belief that Kaepernick hates his country and is unpatriotic (MacDonald, 2019). Here, we see the cancelation-counter-cancelation dynamic.

Following Rosenbaum (2019) we noted differences in how cancelation manifested on Twitter and Instagram, but stopped short of an analysis. Both platforms provided a space for users to voice their moral convictions through online engagement, with social media providing accessibility to the conversation. Through the capabilities of the platforms, i.e., pictures, hashtags and text, online users made their values clear and kept the embers of Kaepernick’s cancelation burning, years after the actual event.

Broader implications of online cancelation

Kaepernick began his protests at the start of the 2016 NFL season, at which point he had already lost his starting position for the San Francisco 49ers, for unrelated reasons. Following his protest, his jersey went from 20th in team sales to the overall number 1 selling jersey in the NFL store (Kaepernick, 2016). Simultaneously and conversely, the withdrawal of support is visible through #colinkaepernicksucksand #cancelcolinkaepernick.

As Rosenbaum (2019: 1) noted, the controversy surrounded “values attached to the national anthem and the flag” with respect and honor as central narratives exemplified by #TakeAStand and #StandForOurAnthem. The military was central, being used by both sides to convey values. On the one hand, #TakeAStand indicated disapproval for Kaepernick’s protest, conversely, #veteransforkaepernick symbolized support for Kaepernick’s right to protest. In 2018, Nike selected Kaepernick as the face of their ad campaign (Evans, 2018). Once again, social media played out two conflicting narratives. The ad featured Kaepernick with the quote, “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.” (Kaepernick, 2018). Some consumers burned Nike apparel in response to the partnership (Evans, 2018). Despite some online backlash, Nike received a bump in online sales by 31% (Edison Trends, 2018).

As has been made evident, the repercussions of cancel culture outlined are not limited to the digital world. Trending hashtags turn to burning apparel, which is again shared online, melding the two (online & offline) worlds.

After a season of protests, Kaepernick opted out of his contract which would have seen him return to the 49ers and after going unsigned by other NFL teams, he has not played since his controversial 2016 season (Schwartz, 2019). In 2019, Kaepernick and the NFL came to a settlement, resolving his 2017 grievance which alleged the NFL colluded against him. Due to a confidentiality agreement, we are not privy to the details (Schwartz, 2019).

That’s now, what’s next?

Athletes have often been spokespeople for social justice movements, using their visibility and platform to address complex societal issues. Attempts by athletes to disrupt the structural imbalances of marginalized and exploited people is referred to as sport-based activism (Cooper, et. al, 2017; Galily, 2019). Muhammad Ali protested the Vietnam War, Olympic runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos protested against racism (Wade, 2016) and Lebron James highlighted violence against POC in response to the deaths of Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner (Lawrence, 2014). Kaepernick wasn’t the first athlete to address controversy, and he will not be the last.

At its best, cancel culture is an accountability tool, enabling marginalized and oppressed communities to shine a light on systemic societal problems. At its worst, cancel culture is a tool wielded by a mass of quasi anonymous users, punishing those deemed to have committed a morally reprehensible act or statement. Social media provided a platform where Kaepernick was simultaneously the subject of cancelation and significant support.

Kaepernick’s cancelation impacted his NFL career, but did not prevent him from highlighting injustices affecting communities of color. Arguably, both the cancelation and the counter-cancelation, established a long-lasting global conversation about not only Kaepernick, but his fight for social justice.

References

- Abramovich, J. [@jacewildspeaker]. (2018, September 7). #VeteransForKaepernick I deployed to Iraq for his right to kneel as is the right of every American to peacefully protest. … [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/jacewildspeaker/status/1037880086156980224

- Ahuvia, A. (2001). Traditional, interpretive, and reception-based content analysis: Improving the ability of content analysis to address issues of pragmatic and theoretical concern. Social Indicators Research, 54, 139–172.

- Bouvier, G. (2020). Racist call-outs and cancel culture on Twitter: The limitations of the platform’s ability to define issues of social justice. Discourse, Context & Media, 38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100431

- Cancian, D. (2020, 8 June) “Everything Donald Trump has said about NFL kneeling so far.” Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/everything-donald-trump-said-nfl-anthem-protests-1509333

- Clark, M. (2020). DRAG THEM: A brief etymology of so-called “cancel culture.” Communication and the Public, 5(3–4), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047320961562

- Cooper, J. N., Macaulay, C., & Rodriguez, S. H. (2017). Race and resistance: A typology of African American sport activism. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(2), 151–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217718170

- D’Souza, D. [@DineshDSouza]. (2020, July 7). Only in a country as prosperous and generous as America can this man consider himself “oppressed.” [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/DineshDSouza/status/1280485159867953153

- Evans, J. (2018, September 4). People are already burning their Nikes in response to the Colin Kaepernick ad: Destroying your stuff to own the libs. Esquire. https://www.esquire.com/style/mens-fashion/a22969808/colin-kaepernick-nike-ad-burning-sneakers-response/

- Galily, Y. (2019). “Shut up and dribble!”? Athletes activism in the age of twittersphere: The case of LeBron James. Technology in Society, 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.01.002

- Hooks, A. M. (2020). Cancel culture: Posthuman hauntologies in digital rhetoric and the latent values of virtual community networks. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/cancel-culture-posthuman-hauntologies-digital/docview/2454696320/se-2

- Jedicke, P. (2020, August 14). “Cancel Culture”: Griffige Definition oder nutzloser Kampfbegriff? Deutsche Welle https://www.dw.com/de/cancel-culture-griffige-definition-oder-nutzloser-kampfbegriff/a-54570483

- Johnson, M. (2016, December 10). Colin Kaepernick’s parents break silence: “We absolutely do support him.” ESPN. https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/18247113/colin-kaepernick-parents-break-silence-speak-support-criticized-quarterback

- Kaepernick, C. D. [@kaepernick7]. (n.d.). Tweets & replies [Twitter profile]. Twitter. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://twitter.com/Kaepernick7

- Kaepernick, C. D. [@kaepernick7]. (n.d.). Posts [Instagram profile]. Instagram. Retrieved July 31, 2021, from https://www.instagram.com/kaepernick7/

- Kaepernick, C. D. [@kaepernick7]. (2016, September 3). I want to thank everyone who has shown me love and support, it truly means a lot! I wasn’t expecting… [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BKDtK_igT3b/

- Kaepernick, C. D. [@kaepernick7]. (2018, September 3.). Believe in something… [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BnRoVQTlFK9/

- Lawrence, M. (2014, December 5). LeBron James takes a stand on Eric Garner, showing how it’s done. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/mitchlawrence/2014/12/05/lebron-james-shows-pro-athletes-how-to-take-a-stand/?sh=4db3b8e84ff9

- MacDonald, J. [@TURNEDTOS1]. (2019, November 25). To the young fans for whom he was a role model Colin Kaepernick sent the message: cops are pigs… [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/TURNEDTOS1/status/1198763893272780801

- McCarn, M. (2016). 49ers Panthers football [Photograph], March, 7, 2022. https://www.mikemccarnphotography.com/gallery-image/Sports/G0000ovBWcmCOvD4/I0000chzFt0zTpJk

- [@nasir.premier]. (2016, August 30). I encourage all veterans to make similar post to mine and show support for our brother Kaepernick. Its a misconception that… [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BJtyAQpAeR6/

- Edisons Trends. (2018, September 7). Nike online sales grew 31% over Labor Day weekend & Kaepernick ad campaign. https://trends.edison.tech/research/nike-labor-day-2018.html

- Ng, E. (2020). No grand pronouncements here…: Reflections on cancel culture and digital media participation. Television & New Media, 21(6), 621–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420918828

- Romano, A. (2020, August 25). Why we can’t stop fighting about cancel culture. Vox https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/12/30/20879720/what-is-cancel-culture-explained-history-debate

- Rosenbaum, J. E. (2019). Degrees of freedom: Exploring agency, narratives, and technological affordances in the #TakeAKnee controversy. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119826125

- Schwartz, N. (2019, February 15). Colin Kaepernick timeline: 22 key moments in Kaepernick’s NFL career. usatoday.com. https://ftw.usatoday.com/2019/02/colin-kaepernick-timeline-22-key-moments-in-kaepernicks-nfl-career

- Wade, P. (2016, August 28). If you burned your Kaepernick jersey, you should burn your Ali poster too: How easily we forget. Esquire. https://www.esquire.com/sports/news/a48080/fans-burning-kaepernick-jersey/?src=socialflowTW

- Wyche, S. (2016, August 27). Colin Kaepernick explains why he sat during national anthem. NFL news. https://www.nfl.com/news/colin-kaepernick-explains-why-he-sat-during-national-anthem-0ap3000000691077

- 10% for the big guy [@Phrygian0]. (2020, July 7). He’s part of the Oppression Industry & it pays very well. #CancelKaepernick #CancelNike #CancelCulture [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Phrygian0/status/1280542772076871680

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Philipp Budka, Monika Palmberger, and Suzana Jovicic for their encouragement, and their generous and valuable feedback on this post.

* Taylor Dube is a master’s student in the program “CREOLE – Cultural Differences and Transnational Processes” at the University of Vienna.