Lea Georgia Locker, Freyja Coreth and Marie Vodicka*

This blog post was created for the seminar “The Materiality and Visuality of Social Media” by Philipp Budka for the MA program “CREOLE – Cultural Differences and Transnational Processes” at the University of Vienna.

We can observe that gender-based violence against women is still present in many aspects of today’s society. Since platforms like Instagram are part of our everyday lives, we stumbled across a post which addresses this topic. That is why we would like to focus on an Instagram post published by the English influencer Lucy Mountain. Her post was a reaction towards the death of the 33-year-old woman Sarah Everard from London. Sarah Everard was kidnapped and killed by a Metropolitan police officer as she was walking home. We decided to use screen recording as a method to visualize the way we engaged with the app’s content.

Being recognized

Lucy Mountain’s Instagram post opened a space of discussion and exchange, particularly for women who stand in solidarity with everyone who fears violence from men.

We want to discuss how people engaged with the post by the English influencer. For that purpose, we collected data through participant observation on Instagram, as well as offline in the form of narrative interviews. We organized interviews with five users who engaged with the post, three cis women and two cis men. During the interviews we showed them screenshots we took to see how they felt about certain comments. Following on from that we were able to create categories about the types of engagement users showed.

Gaining an understanding of digital activism on Instagram

The murder of Sarah Everard caused a wave of grief and led to a confrontation with deeply rooted gender inequalities. With the post regarding Everard’s death, Lucy Mountain connected millions of people who have been following her.

The speech bubble we can see in Lucy Mountain’s post is a message that she sent to a person. In doing so, she uses a private conversation that takes place between two people to open a political discussion on the semi- public platform Instagram, which is part of the Meta group. While non-registered users can only engage with public accounts and their content to a certain extent, registered users can engage with all the content that is provided on the app, as long as a profile is not private.

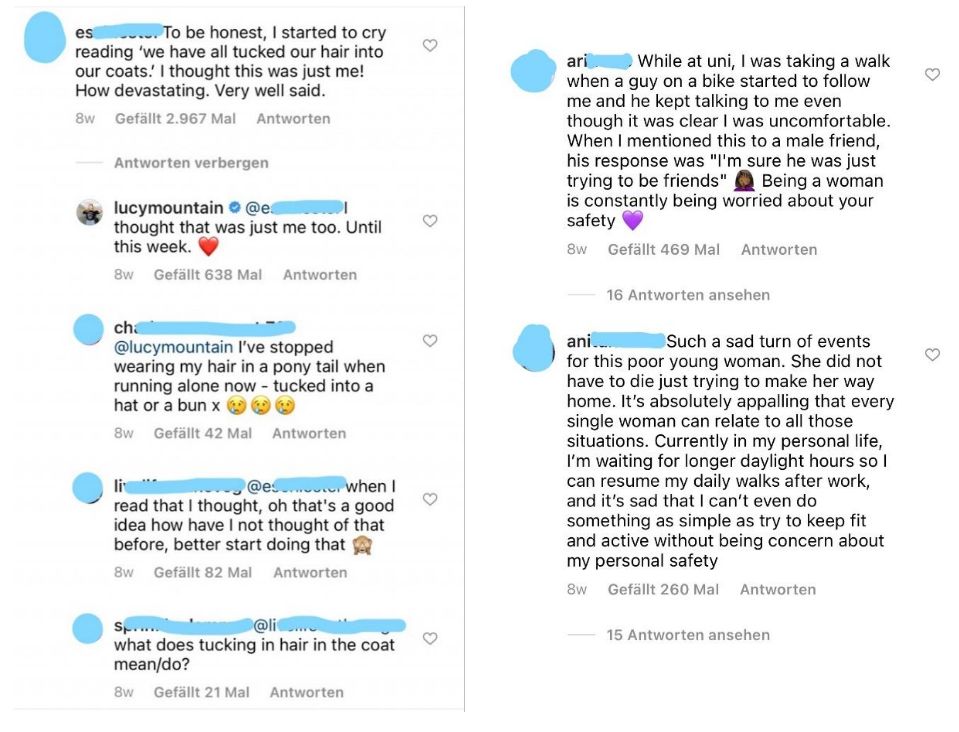

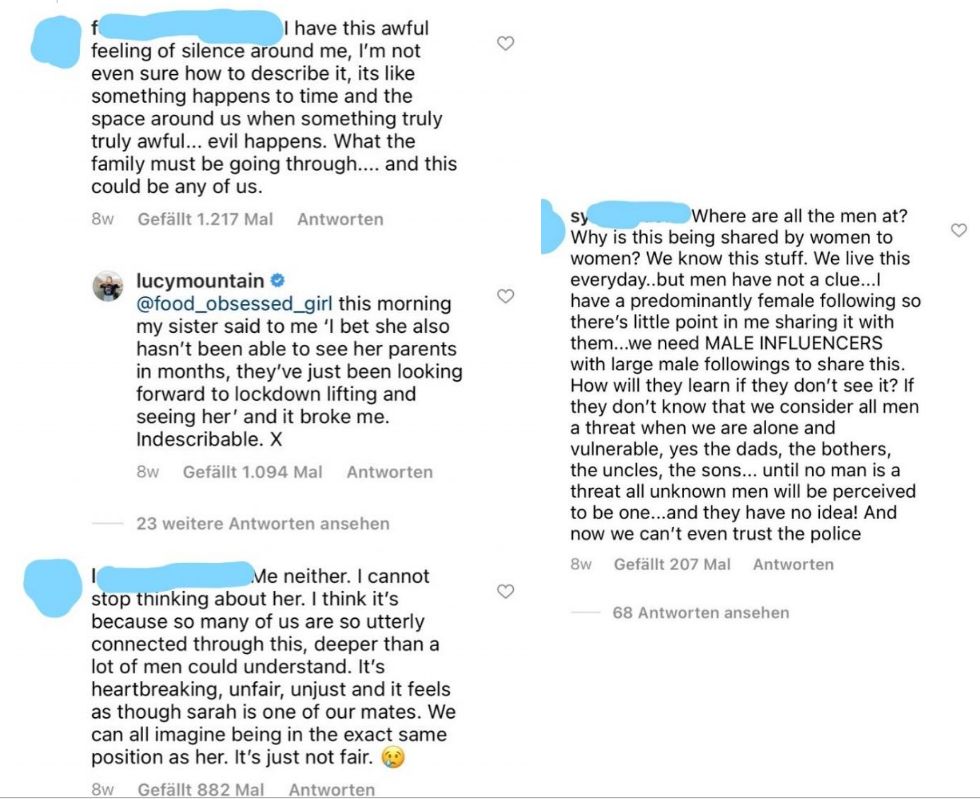

Going on from this, it is interesting to observe how the comment section was used by Lucy Mountain and users for exchange. Here, the liking of posts can be read as a form of approval, whereas comments give the option to articulate all kinds of different reactions. Both forms of exchange lead to a sense of belonging and users turn from being passive readers to active participants.

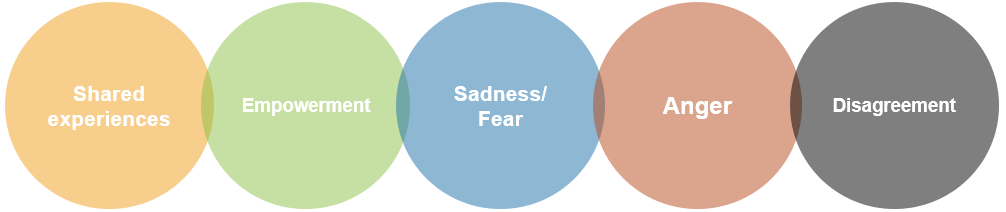

We used this form of exchange to decide which comments would be interesting for us. We decided to focus on comments with either a lot of interaction through replies or through likes. After reading hundreds of comments and conducting interviews we formed five categories: Shared Experiences, Empowerment, Anger, Sadness/Fear, and Disagreement.

Creating a connection

Our interviewees repeatedly pointed out how much sharing of common experiences helps them to deal with negative experiences.

Later, when I got to the post through other reposts, the caption really spoke to me. She calls it a standard procedure among women and an autopilot mode, and this is so relatable for me. We (women) go through similar or same stuff in this situation. […] And I found it so powerful how she said that we all have held our keys between our fingers because that is exactly what I did when I used to work in a restaurant and had to go home at night.

(Excerpt (NS – she/her) from interview, 27th of May 2021)

Walking home alone in the fear of getting attacked describes the so-called tacit knowledge. This form of knowledge can be understood as the unspoken but ever-present struggle women have to face. A situation that mainly affects the individual, while the idea of explicit knowledge describes an urgent topic that collectively affects a certain group of people (cf. Ahmad, 2019: 179). As in our example, this would be women’s safety within public spaces. Because this knowledge is shared by several people, it becomes more publicly available. This pattern can be seen in the comment section of the post.

Through the sharing of individual experiences in public, the post became a shared, freely accessible catalogue of knowledge. As a result, women who might have felt invisible before were gaining visibility. By that they were having a chance to transparently address an issue they are struggling with.

Reactions build on each other

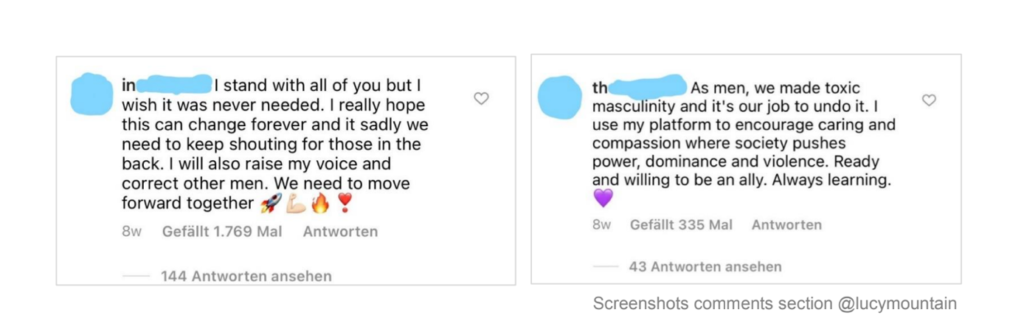

Taking a closer look at Empowerment, we noticed how men were expressing their solidarity with and compassion for women.

The support they showed was a reaction towards Shared Experiences. After male users read through the explicit knowledge of women, people addressed their support both within the digital sphere as well as in the physical world. Our example reflects the notion that online and offline do not exist separately, as argued by Miller and colleagues (2016: 7).

It was not the post itself that was able to create this space, it was the people who read, understood, and interacted with it. They created a safe space where relations were developed, socio-political problems were addressed, and prospective allies and supporters were found.

Emotional spectrum

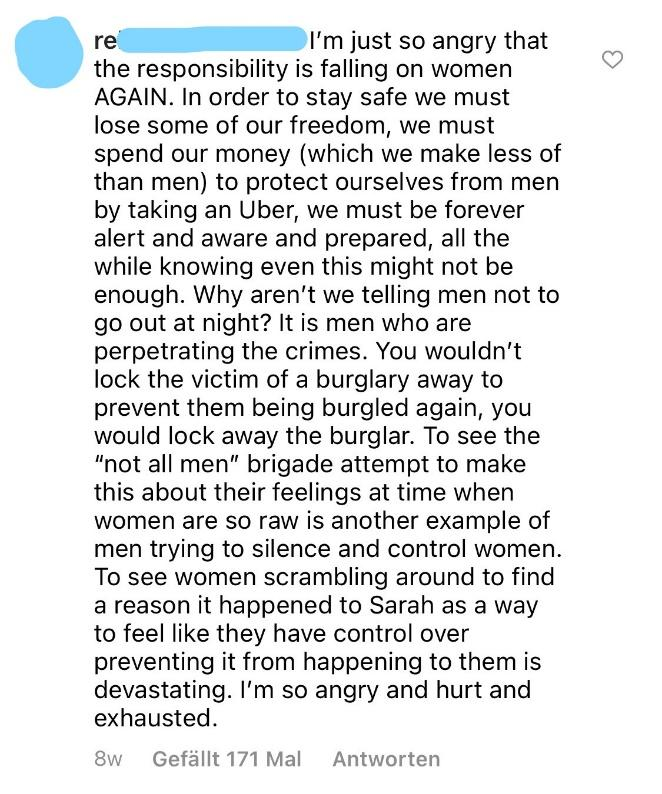

Like Empowerment, Anger is built upon other emotions. By expressing anger, users are addressing their emotional connection to this topic, no matter which of the other main sentiments their message actually falls into.

As seen in the screenshot, women were using the post to address their wish for social change. In doing so they were demanding education on the topic of sexual harassment beyond women.

Elena Pavan describes this kind of exchange through social media very precisely: it is a so-called integrative power which implies a sociotechnical force that is built upon the interaction between social media and the human need for social change (Pavan, 2017: 438).

In the digital age, beside persistent challenges to gender equality, there is also a pressing need to recognize and fight old and new gender-based abuses perpetrated dynamically across the online/offline boundary.

(Pavan, 2017: 438)

Infrastructures that are being offered by platforms like Instagram enable interaction between its users. As a consequence, communication leads them to build networks of collective actions. Instagram can be visualized as a space shaped by its infrastructures such as tools to like, share, repost or comment content. Thereby potential to create a discourse or more specifically a place of interaction arises (Pavan, 2017: 434). Especially with regards to activism, the app offers a basis that allows users to create new strategies to become politically active.

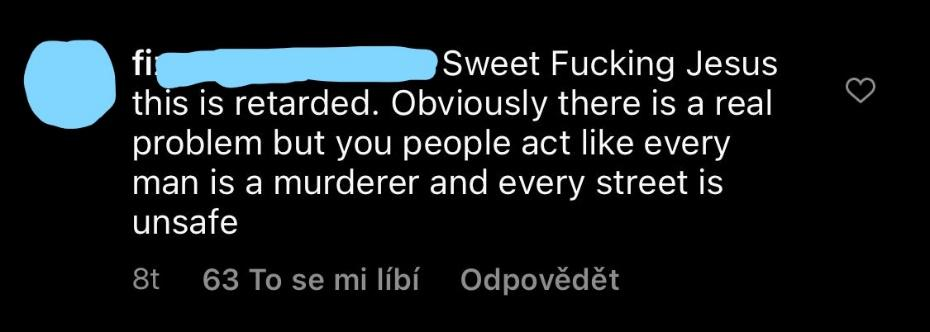

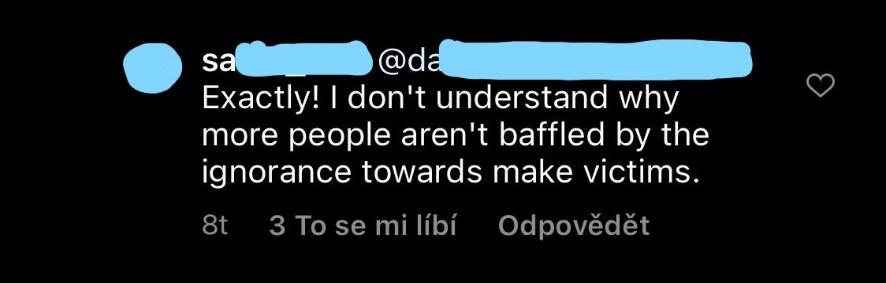

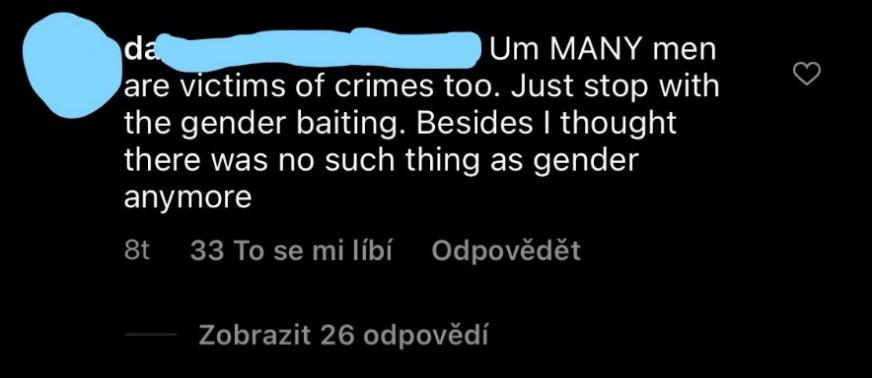

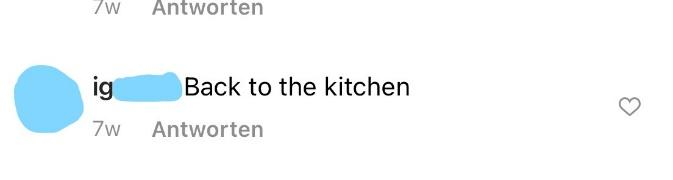

Since anger can be understood as a form of expression to address several other emotions or thoughts, Disagreement naturally leans on it. Through this, comments that are rather negative towards the debate are also formulated.

Disagreement was expressed several times. Interestingly, most of these users’ profiles, as well as their engagement with the post were structured similarly:

• Almost none of the users responded to further discussions.

• Users usually had no or only cryptic profile photos.

• They only had a few to no followers.

• They had no private posts on their own profiles.

It is possible that rather than engaging with the content, some of these users were more interested in the interactional aspect of the exchange: sabotaging the discussion or triggering other users, or gaining attention.

The red thread

The analytical category of Sadness/Fear reflects on deeply rooted emotions. When we compared our interviews and the rest of the collected data, we found that these emotions can be understood as the origin of the debate. Women are left with the feeling of everlasting fear which seems unavoidable. Going further to say that no matter what precautions they take, women feel they are at the mercy of men.

What can we take away?

Lucy Mountain’s post went viral while becoming a symbol of awareness for millions of her followers. This encouraged thousands of users of all genders to interact with the post through likes, reposts, or comments.

Some of them expressed their grief and sadness. Others reacted with anger and sought for social justice. And yet others took a stand for empowerment of women.

Platforms like Instagram offer an infrastructure for their users that is bound to technical and to policy limitations. Instagram can be used for a specific purpose such as drawing attention to socio-politically relevant issues. While registered users are given a chance to collectively create a space of (political) knowledge sharing (comment, like, repost), non-registered people can view and share the post.

What came up throughout the process of analyzing was that we were not only encountering stories, but we were also eliciting and co-creating them.

In attempts to create a complete picture, the risk of overgeneralizing popped up every now and then. But according to Tom Boellstorff (2012: 177) ethnographers should not be frightened to discover schemes and, beyond that, to locate them within broader relations such as the relation between Instagram and activism.

As female researchers we noticed how angry the topic made us feel. By following our feelings, we eventually could change sentiments of frustration into something significant like empowerment.

Unfortunately, academic content often remains exactly where it is produced – within universities. A fact that we believe to be counterproductive and outdated. Therefore, we have set ourselves the goal of publishing the content of our research in a way that is accessible to everyone.

We found it necessary to include the analytical category of disagreement in our analysis to present comprehensive and representative data, but we do not resonate in any way with the statements made there. It is perfectly normal to have several opinions about a topic within a controversial debate. Still – what we can see in the section disagreement is a reproduction of stereotypes and the downplaying of a very distinct issue.

We are aware of the fact, that as anthropologists we are in a position to act “like a fly on the wall” when it comes to analyzing our respective field, but beyond being anthropologists, as humans, and as women we are affected by these structures.

References

- Ahmad, N. (2019). The Internet, Social Media, and Knowledge Production and Development of Political Marketing. In Ahmad, Nyarwi (Ed.): The Internet, Social Media, and Knowledge Production and Development of Political Marketing: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications (pp.177-208). Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7669-3.ch028.

- Boellstorff, T. et al. (Eds.). (2012). Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton: University Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12038_2.

- Miller, D. (2016). The Future. In Miller, D.et al. (Eds.). How the World changed Social Media. (pp.205-216). London. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781910634493.

- Pavan, E. (2017). The integrative power of online collective action networks beyond protest. Exploring social media use in the process of institutionalization, Social Movement Studies, 16:4. Italy. (pp.433-446). https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2016.1268956.

* The authors are master’s students in the program “CREOLE” at the University of Vienna.