Sophie Colas**

Engagement with digital technology takes numerous, often very abstract and tenuous forms that sometimes involve the intervention of other people. Such multiple engagement with digital technology appears to be particularly relevant in old age but would probably apply to other age groups likewise. While studying how elderly Parisians engage with ICT (Information and Communication Technology), I have come to realize that it is worth considering situations in which the internet is used through the assistance of others as these situations are also significant. From the beginning of my research, I have encountered many situations in which the elderly person’s relationship with technology differs from what could have been imagined as a “digital life” at a first glance. They have nonetheless turned out quite substantial.

Since Autumn of 2019, when I started my doctoral project, I have been exploring how elderly people in Paris engage with ICT. My research thus addresses the topics of both aging and technological experiences in an urban area. It sets out to investigate the biographical, societal, and physical changes that occur over one’s lifetime, particularly in old age, and the effects that they can have on a person’s technologized life. By focusing on a population that has long lived without digital technology and has had to adjust to a new digital era, I aim to reflect on our relationship to digital technology as a society and on how digital platforms have become so embedded in our lives. Like many other societies, French society is digitalizing at great speed: administrative services, businesses, and interpersonal communications are increasingly introducing digital technology. Until fairly recently, most of my research participants would use so-called “traditional” methods to communicate and keep up to date on the latest news, for example the radio, the landline or the television. Exploring their singular experience with digital technology could expose the way we take living in a digital society for granted.

Studying the various modes of digital intersection with an elderly person’s life would require a certain intimacy and ability to observe his or her daily life over a long period of time. Building this intimacy enables the researcher to become privy to the participants’ relationship with digital technology and be able to contextualize it, as Palmberger and Budka (2020) previously put it in this blog series. In that respect, as part of my study, I have shared somewhat banal moments of daily life with elderly Parisians. I give them a call, pay them a visit, help them with grocery shopping or household chores, generally keeping myself informed of what occurs in their lives. Often, I hear about their pains, sorrows, and expectations about life, their surroundings, and the future. The field data generated thus far should help me better understand how digital technology can affect people in their older age.

Beyond a user/non-user framework: post-userism?

From that research with the elderly population of Paris, it soon became clear that the digital life of individuals does not limit itself to just using a computer or smartphone. Beyond those “concrete” and easily observable types of engagement with ICT, evidence shows that digital technology intervenes in and shapes people’s lives in many other ways. Yet, these subtle intersections of the internet with daily life can sometimes remain unnoticed. Therefore, it was essential in my research to pay attention to all these ways in which digital technology is embedded; not only the most evident and materialized aspects of it (logging into a social network account or using a tablet to upload some photographs) but also the more subtle ones (for example having your medical appointments arranged by someone via an online healthcare service).

At the early stage of my research, I addressed elderly people’s relationships with digital technology through a dichotomic user / non-user framework, before realizing it would not capture the full spectrum of interactions between digital technology and elderly Parisians. Nowadays, technology is so ubiquitous, “embedded, embodied and everyday” as Hine states (2015: 23) and mundane (Pink et al., 2017), that studying how it shapes our daily lives can turn out to be quite challenging.

The post-userism HCI (Human and Computer Interaction studies) body of research (Braumer & Brubacker, 2017) has provided meaningful contributions around this matter by pointing out the limits of, and suggesting alternatives to, the commonly accepted idea of a “user” in internet studies. The post-userism perspective evidences that due to cost, lack of digital literacy, or eventual physical impairment, people can at times be constrained in their interactions with technology and must employ the help of intermediaries. Besides, social media profiles can be used by several individuals at once even though the computer system does not differentiate between them (i.e. when a deceased person’s profile is turned into a memorial by their relatives, or when a couple shares the same account).

According to the post-userism perspective, the concept of “user” should be reconsidered to better include individuals’ different appropriations of and adjustments to technology. Following this approach, we should rather adopt the term “post-user”. However, we can still ask ourselves what that term opens and obscures, as using digital technology through other people (intermediaries) always implies the existence of a user (in the original sense). Perhaps, the concept of “user” and the idea of “going online” could instead be considered from a broader perspective to encompass all the ways in which people and digital technology interact and mutually adjust to each other.

Michèle and Souad

I would now like to illustrate my statement with a couple of specific cases extracted from my fieldwork, including those of Michèle and Souad (both pseudonyms).

Michèle is a visually impaired 87-year-old woman who describes herself as completely inept when it comes to digital technology. Living alone in a small flat in the northern outskirts of Paris, Michèle no longer possesses any digital devices, and only uses her landline and cellphone (she did own a tablet for a few years before passing it on to her niece when her eyesight dramatically worsened). However, I did not find her as disconnected as she claimed to be. For a while now, technology has been present in her life through the intermediary of surrogate users, a workaround already mapped out by Pype (2017) in her research on intergenerational relationships and the use of ICT in Kinshasa, Congo. Michèle has in fact relied on the weekly visits of her cleaner and physiotherapist to get the information she needs from the internet. Michèle regularly takes advantage of having them around to look up the opening hours of shops or municipal services online.

Souad’s experience with technology can be compared to Michèle’s. This 89-year-old woman living in subsidized housing located in a former working-class district of Paris has seen her nervous system seriously afflicted, preventing her from properly using her smartphone. Following a back surgery and as a result of the hard years spent working as a seamstress, cashier, and nanny, Souad now suffers from severe hand tremors and frequent memory lapses that impact her use of technology. In spite of her physical impairments, Souad keeps using her phone. She lies down in bed, wedges the device between her neck and shoulder, and contacts relatives several times a day. As for text messages and emails, Souad solicits the help of a janitor working in her building who reads her messages out loud and replies on her behalf.

The experiences these two women have with digital technology are sustained through their relationships with caregivers or people from their community. Their stories are anything but out of the ordinary. On the contrary, these research cases are telling examples of the forms which digital engagement can take at a later stage in life. In the cases of Souad and Michèle, a dichotomic user/non-user framework, would have failed to recognize how these two women access the internet and maintain a presence online.

Doctolib, Maiia and Keldoc

The current health crisis and its related politics also offer numerous examples where the Internet intercepts with someone’s life. The vaccination campaigns are indeed particularly revealing in respect to how digital technology plays in an elderly person’s life, as they require a fluid relationship with technology. At the beginning of 2021, the Covid-19 vaccination program was rolled out in France. Due to the scarcity of available vaccines, the French government prioritized people aged over 75, as well as younger people with additional risk factors. To register for the vaccine, two options were made available. Either to dial a national call line, which rapidly became oversaturated, to be added to a waiting list, or to find an available slot on different medical appointment scheduling apps. For the sake of the Covid-19 vaccination campaign, three apps were appointed by the French government to facilitate registration: Doctolib, Keldoc, and Maiia. Opting for such apps implies feeling sufficiently comfortable with digital technology or being able to mobilize an internet-savvy person to book an appointment on one’s behalf (they could be a relative, a neighbor, a medical caregiver, etc.). Michèle and Souad, as many of my research interlocutors, had to do the latter. These two elderly women and others have managed to get on the list for the next available injections, without themselves having to use any medical consultation apps.

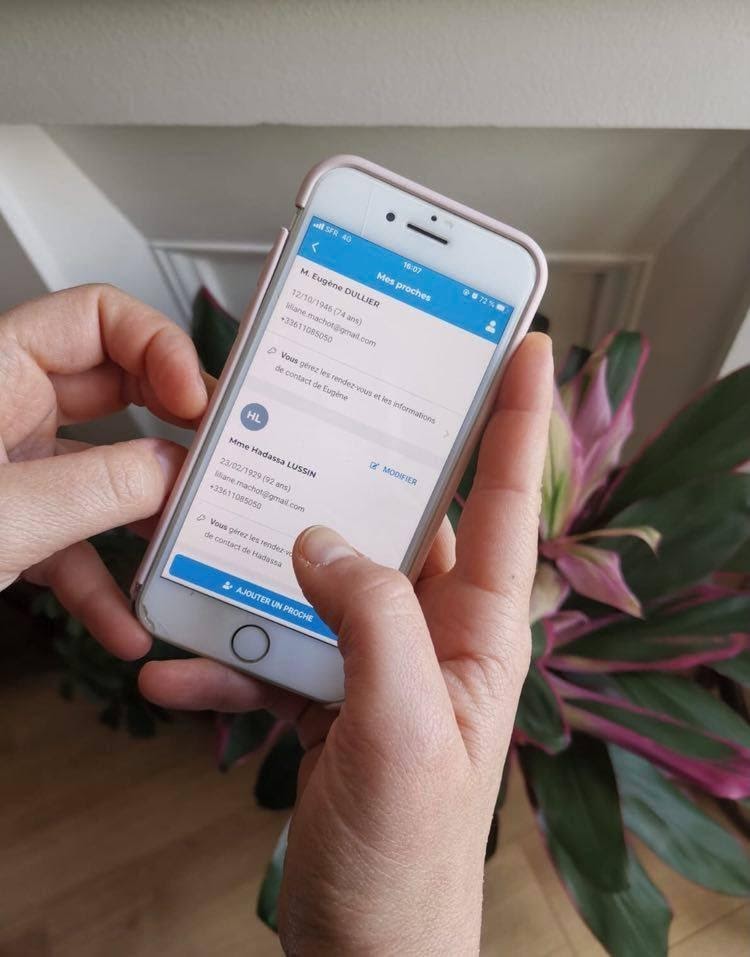

These apps are used by intermediaries on someone else’s behalf outside of the context of the Covid-19 pandemic too. Since these interfaces with doctors have become very popular, some creative uses have emerged. Over the course of my research, I have met a self-employed nurse who uses her private Doctolib account for the option it provides to create several profiles and arrange medical appointments for her older patients. By opening the app, she can access the six profiles that she has set up to facilitate her care recipients’ consultations with medical practitioners. In doing so, she acts as an intermediary between elderly patients and newly digitized health care services.

Engaging with digital technology

Referring to the case studies above, I have brought attention to how digital technology can make itself present in elderly Parisians’ everyday life without them necessarily sitting behind a keyboard or browsing the Internet without assistance. As Braumer and Brubacker (2017), as well as Pype (2017), contend, and as my ongoing research has already demonstrated, the concept of “user” imposes strong limitations on a reality that is not as straightforward.

In France, the elderly population is often thought to be estranged from digital technology. Nevertheless, it would not be true to make them out as completely disconnected from the internet, as I highlighted with my ethnographic vignettes. On the contrary, the elderly in Paris encounter and interact with the digital world in numerous ways, although not always through a direct use of a smartphone or a computer. Moreover, elderly Parisians have proven to be a great source of creation and appropriation where new digital technologies are concerned. In an increasingly digitalized world, elderly Parisians deal with, negotiate and tinker with digital devices, platforms and services all the time.

Building on my research with the elderly population of Paris, my point in this blog post was to encourage fellow researchers to consider the different types of engagement that can occur with digital technology: be it through intermediaries or even more indirectly. Accounting for these diverse modes of digital engagement may require multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork or the combination of several research methods. In any case, what seems fundamental is to take into consideration all the different ways in which digital technology is embedded into someone’s life since one type of engagement with digital technology cannot be understood without considering the others. Studying individuals’ engagement with digital technology necessitates a holistic approach and a broader conception of the user’s situation and position. A concept that goes beyond the traditional notion of use that does not account for all realities.

References

- Baumer, E. P., & Brubaker, J. R. (2017, May). Post-userism. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 6291-6303). https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025740

- Hine, C. (2015). Ethnography for the internet: Embedded, embodied and everyday. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003085348

- Pink, S., Sumartojo, S., Lupton, D., & Heyes La Bond, C. (2017). Mundane data: The routines, contingencies and accomplishments of digital living. Big Data & Society, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717700924

- Pype, K. (2017). Brokers of belonging: Kinshasa’s elders, mobile phones and intermediaries. In: W. Mano & W. Willems (eds.), Everyday media culture in Africa: Audience and users (pp. 198-219). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315472775

- Palmberger, M., & Budka, P. (2020, November 13). Collaborative ethnography in the digital age: Towards a new methodological framework. Digital Ethnography Initiative Blog. https://digitalethnography.at/2020/11/13/collaborative-ethnography-in-the-digital-age-towards-a-new-methodological-framework/

Acknowledgement

I thank Suzana Jovicic, Monika Palmberger and Philipp Budka for offering me the chance to write in this blog and for their insightful comments on this text. Moreover, I am very grateful to my friends Eva Roy and Elisabeth Reisenauer for their corrections and precious suggestions.

* This contribution builds on the questions raised by Monika Palmberger and Philipp Budka in the first post of the blog post series “DEI Dialogues”.

Preferred citation: Colas, S. (2021, June 24). Aging in a digitalized world: Beyond a user/non-user framework. Digital Ethnography Initiative Blog. https://digitalethnography.at/2021/06/24/aging-in-a-digitalized-world-beyond-a-user-non-user-framework

** Sophie Colas is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology and Anthropology at both University of Lille (France) and KU Leuven University (Belgium). Since 2019 she has been researching elderly people’s relationship with digital technology in the city of Paris.

One thought on “Aging in a Digitalized World: Beyond a User/Non-User Framework*”