Alice Roberte de Oliveira*

Introduction

Ethnography is crafted from field experiences, and each one is unique. Sharing particularities might help other colleagues diversify their data gathering. In my ongoing PhD in Communication Studies, gathering Google Reviews was a new way of engaging with the field and bringing texture to my research. By revealing personal experiences, online comments and ratings can add layers of detail and nuance that enrich an ethnography with further insights and stories, as it did with mine.

Google Reviews allows customers to comment on business, service, or place and rate it on a scale of 1 to 5 stars. Customers can leave detailed feedback describing their experience or general impressions regarding the service quality. Users can also attach photos to give additional context to their review. Businesses can publicly respond to the reviews, engaging with customers, addressing concerns, or thanking them for their feedback. Reviews are tied to a specific address and appear on Google Maps alongside the business details.

Online reviews, as a way of measuring reputation and sentiment, are used in marketing and tourism fields, especially within research that draws on the netnography method (see Alzboun et al, 2023; Nayak et al 2023; Alam et al, 2024). It is also used as “geodemographic data” in surveillance and urban studies that conduct “contemporary datafied urban ethnographies” (Trottier et al 2021: 313). My study is more aligned with this latter body of research. Academics from these fields are aware of the ethical implications of neighbourhood knowledge production and representation, and they advocate for in-person fieldwork to prevent the misalignment of reviews and residents’ experiences (Trottier et al 2021). Therefore, this approach requires careful consideration of the ethical issues and methodological challenges, just like any other method.

My research is an ethnography of a residential block in Brasília, Brazil’s Capital, conducted between April 2023 and September 2024. It discusses how the digital entwines material infrastructure, bureaucracy, pet ownership, residents’ sociality and home interiors. Participant observation was the core of the fieldwork, but engagement with digital artefacts became relevant to explore different dimensions of my object. Similar to research that explores the digital aspect of neighbourhoods (Lane, 2019; Bottino, 2022), my study demanded a “multi-modal ethnography”, with in-person and online data gathering (see Hine, 2015).

Digital Ecology

I found out that various topics are articulated through different digital sources: the block’s email address, the block’s internal software (for tax invoices and meetings), Instagram profiles of the block, broadcast lists and groups on WhatsApp, and reviews on Google. Residents use these digital artefacts to fulfil their collective and private needs, such as those related to infrastructure, the selling of items, the sharing of random information, or asking for help in emergencies. These digital artefacts constitute the block’s “digital ecology” and are interconnected in what Madianou and Miller (2021) conceptualised as a “polymedia” relationship–meaning that they are relationally integrated, and people choose to use them based not only on their affordances but also on moral and emotional considerations.

That Google Reviews form part of the “digital ecology” of the block was reaffirmed when I was navigating a chat group on WhatsApp. I came across a resident who resorted to different channels, including Google Reviews, to complain about infrastructural issues with the property manager. He demanded that correct signs be displayed in the garage to avoid damage to his motorcycle. Thereby he was not only attempting to draw the property manager’s attention, but he was also presumably trying to impact the block’s public image.

This episode raised questions: to what extent do reviews accurately reflect the dwelling experience in the block, and what are their implications? In this post, I explain how I extracted ratings and comments and quantitatively evaluated them. I argue that this method gave me a preliminary overview of the block’s reputation, which would later supplement qualitative data further developed in my thesis.

Gathering Reviews

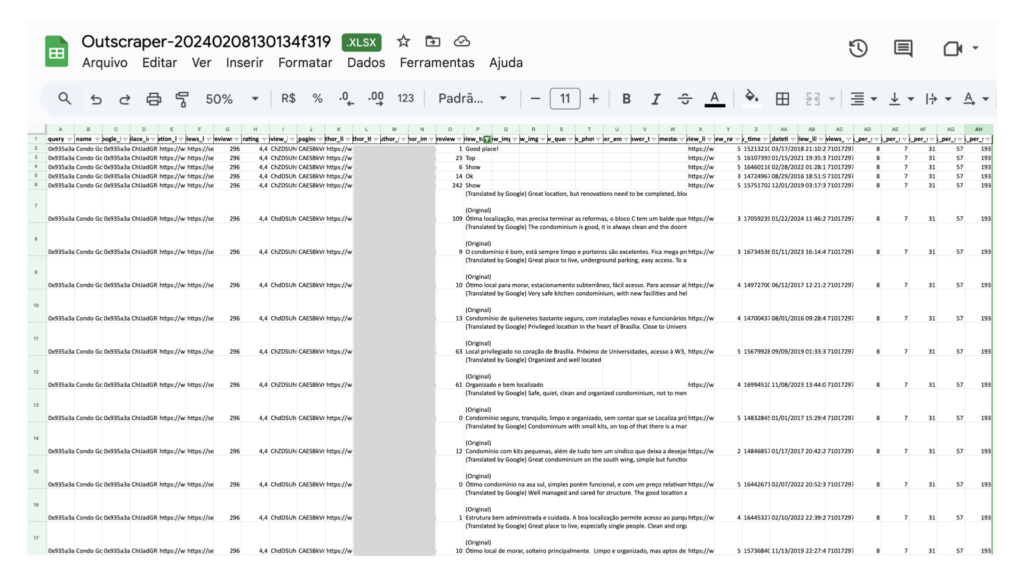

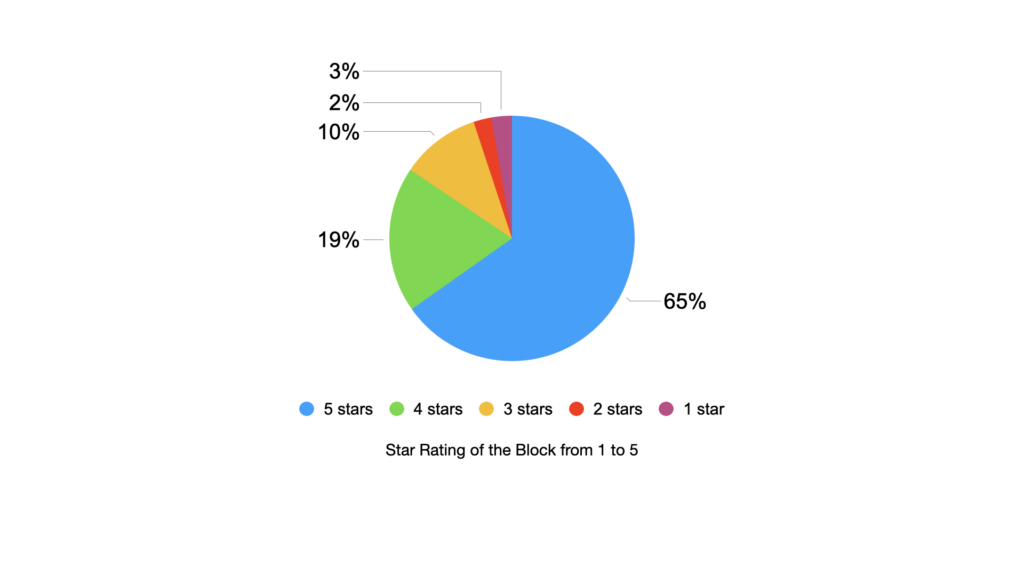

By the end of fieldwork, the block had 296 reviews (including comments and ratings from 1 to 5). A friend of mine who is a programmer used Outscraper to help me extract all the reviews tied to the block’s address at that time. These were organised into a spreadsheet (Image 1) with the author’s profile, date and time of the review, a link to the review, replies from the owner, review likes, and review ratings. It also included author review counts (a rating system that attributes trust to users based on the number of reviews they gave on Google), among other information. I extracted the reviews in Portuguese, the language in which they were written, but also in English since it was configured as the language of my account. I organised the ratings from 1 to 5 stars into a graph (Image 2) to visualise it. The stars compound an average rating of 4.4 out of 5 at the time.

Quantitative Evaluation of Comments

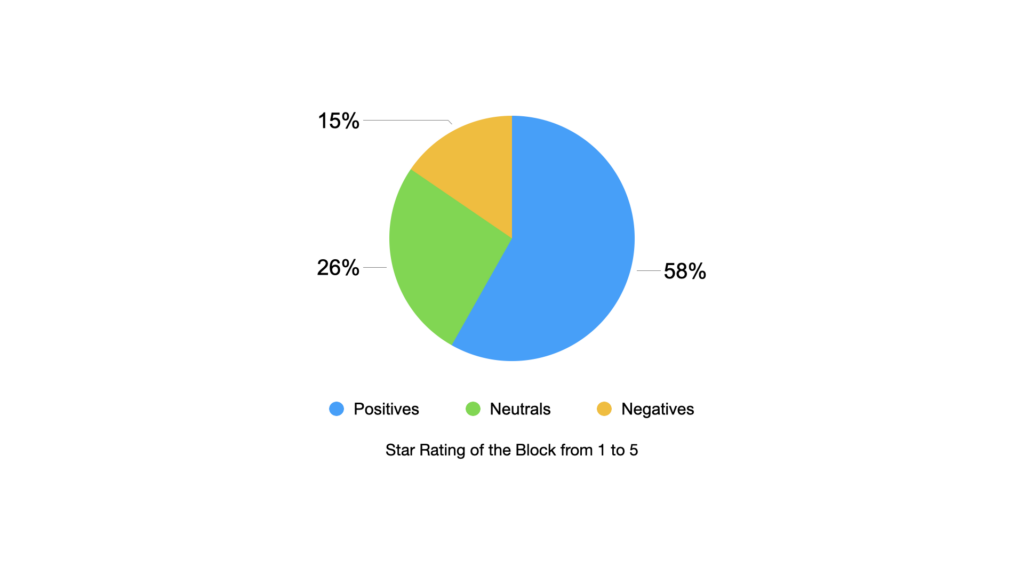

The block received a total of 110 text reviews. Even with the data being public on Google, I separated the comments into another sheet, excluding any personal information such as name and email, as well as the block’s characteristics, to avoid bringing harm to the community. I performed a technique inspired by the “sentiment analysis” method (Feldman, 2013), which uses machine learning and language patterns to categorise emotional tones in writing (as either positive, negative or neutral). I used the free version of Chat GPT 4.0 to speed up the evaluation. My prompt was: “Analyse the comments by categorising them as positive, negative, or neutral. Indicate the number of comments that fall into each category. Comments cannot be included in more than one category, as the categories are mutually exclusive. I will provide the comments below”. After prompting, I copied and pasted the comments into Chat GPT 4.0.

Most of the impressions were positive or neutral (84%) and above four stars (84%), apparently indicating a high level of general satisfaction with the block (Image 3).

Findings and Future Work

The average rating of the block on Google Reviews was 4.4. In isolation, this says little about the block. Online reviews should be interpreted within the broader context that a multi-modal ethnography can provide. As Coleman (2010) stated, ethnography brings context and cultural meaning to digital media uses.

Online reviews can give insight into various interests and power disputes. For instance, to be able to respond to comments as they are made, the block must have a business account on Google and, consequently, someone, usually the property manager, must be in charge of it. The role of the manager changes over time and is subject to the property owners’ scrutiny. In this sense, a deeper analysis must consider the year the comments were written, who was in charge at the time and what their relationships were. This could help to understand if positive or negative reviews from residents were an attempt to overestimate or retaliate against the property manager because of a personal conflict, like the example I presented earlier. Ratings and comments, in this sense, can give clues not just about external reputation but about internal politics.

This exercise also highlights concerns about digital technology biases and ethical issues surrounding Google Reviews and Chat GPT. As academics have argued, online reviews can sometimes impact individuals and communities, who may be identified, potentially resulting in abuse and exploitation (Trottier et al 2021). The entanglement of “localised knowledge” (such as that of the reviewers) with a global platform (like Google) needs to be critically considered, as it can obscure facts and flatten complex contexts (Trottier et al 2021).

Chat GPT was used as a test to expedite a quantitative overview of the block’s reputation but also requires further analysis. For example, positive, negative, and neutral categories need to be contextualised rather than naturalised. One solution would be to invest time in training the software before requesting a quantitative summary.

To conclude, living in a flat block today is more than simply inhabiting a material infrastructure. It is constituted by a multitude of seemingly ordinary digital experiences, such as leaving ratings and text reviews about the locality on Google. These online reviews may express approval or dissatisfaction, but they also encode interests, politics and affect the reputation of an asset. Google Reviews, therefore, can be an ethnographic tool for developing a more comprehensive understanding of life in residential blocks.

References

- Alam, A., Ratnasari, R. T., Al Hakim, M. H., Mutmainah, S., & Mufidah, A. (2024). Comparative netnographic analysis of sharia hotel visitor reviews between tripadvisor and google review. Multidisciplinary Reviews, 7(7), 2024151. https://doi.org/10.31893/multirev.2024151

- Alzboun, Nidal & Alhur, Mohammad & Khawaldah, Hamzah & Alshurideh, Muhammad. (2023). Assessing gastronomic tourism using machine learning approach: The case of google review. 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2023.5.010

- Bottino, C. M. M. (2022). A vizinhança tá on: o protagonismo das mídias sociais em um condomínio clube no subúrbio do Rio de Janeiro. 2022. 200 f. Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia, Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, 2022. https://app.uff.br/riuff;handlle/handle/1/34414.

- Coleman, G. E. (2010). Ethnographic Approaches to Digital Media. Annual Review of Anthropology – Volume 39, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104945

- Feldman R., Techniques and applications for sentiment analysis, Commun. ACM 56 (4) (2013) 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1145/2436256.2436274

- Hine, C. (2015). Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and everyday. Bloomsbury.

- Lane, J. (2019) The Digital Street. Oxford University Press.

- Madianou, M., & Miller, D. (2013). Polymedia: Towards a new theory of digital media in interpersonal communication. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 16(2), 169-187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912452486.

- Nayak, N., Polus, R., & Piramanayagam, S. (2023). What can online reviews reveal about Tourism Destination Image? A netnographic approach to a pilgrim destination in India. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(6), 1284–1300. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2160921

- Trottier, D., Lee, J. & Boy, J. (2021). Urban Data Analytics as Research Topic, Method and Ethical Concern. Digital Culture & Society, 7(2), 311-328. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2021-070215

Acknowledgment

I am grateful for the comments provided by the editorial team of this blog.

*Alice Roberte de Oliveira is a PhD Candidate in the Faculty of Communication at the University of Brasília (UnB), Brazil. Research Fellow at the Centre for Digital Anthropology at UCL (2023-2024), where she conducted part of her research, supported by CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, Brasília – DF. Served as a Volunteer Professor at the Communication Department of UnB (2021). Holds an MA in Communication (UnB, 2019) and a BA in Advertisement (UnB, 2014).

E-mail: aliceroberte(at)gmail.com; alice.roberte(at)fac.unb.br

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9815-2368 | X: https://x.com/AliceRoberte