Luise Erbentraut*

With smartphones becoming an integral part of how people navigate and experience their interpersonal relationships, visuality has assumed a central role. The fusion of camera and communication technology embeds images and photography as practices within personal and intimate relationships. This also includes the consensual sharing of “nudes”, which are commonly known as photographic self-portraits of the partially or fully unclothed body (Albury & Crawford, 2012).

As they involve intimate aspects of individuals’ bodies, identities, and relations, and raise concerns about potential misuse, nudes are an inherently sensitive research topic. Thus, engaging with nudes in ethnographic research raises important methodological and ethical questions. Yet, queer nudes introduce specific challenges when it comes to the ambivalence of (in)visibility: They are deeply personal but also emerge within a community in which visibility is both a political demand and a tool. In this blog post, I build on this dual tension of (in)visibility, to glance at Photo-Elicitation Interviews with image-generating AI as a collaborative and reflexive methodological approach.

Researching (in)visible pictures

The question of (in)visibility of nudes has accompanied my research from the very beginning. By investigating the aesthetic, technical and emotional dimensions of queer nudes, I engage with participants who self-identify as part of the LGBTIQ+ community, are over 18 years old, and are dispersed across urban spaces of Germany. The initial conversation – whether via chat, phone, email, or in person – follows broadly a similar pattern: After a brief summary of the project, my conversation partners cautiously ask whether their own images would be expected as part of the interviews. While this recurring hesitation speaks to the intimate facet inherent in nudes, it also points to a broader ambivalence surrounding the visibility of queer bodies and practices.

In queer activism and scholarship, visibility is often framed as a political instrument. Yet, as Schaffer (2008) elaborates, it is not universally perceived as empowerment. Further, she argues invisibility can even function as a queer survival strategy (ibid. 54). To respond to participants’ hesitation, visual ethnography offers Photo-Elicitation Interviews (PEI) as a way to engage with visual practices without necessarily exposing personal imagery. In PEI, images first and foremost serve as a starting point to gain deeper insights into participants’ experiences (Harper, 2002). One key advantage of integrating images in interview settings is that they act as memory aids to stimulate reflections about visual practices and the emotional experiences surrounding them (Fawns, 2021). From this perspective, the affective and social relations – such as the emotions which accompany the process of taking specific pictures or the relationships the pictures tell about – pointing beyond images can be researched without the images themselves becoming part of the research data. Drawing from this strength of PEI, in my case, the pictures are used exclusively as “interview stimulus” (Wagner, 1978 in Harper, 2002, 15) to spark participants’ reflection on their own visual practices. During the Zoom meetings participants may take a look at their smartphones laying besides their laptop or computer, without me – on the other side of Zoom – seeing the pictures. This approach enables an exploration of practical and emotional aspects of queer nudes while navigating participants’ vulnerability regarding the visibility of their images. Yet, this raises the challenge of how to explore the visual facets of the image practice, such as perspective, posing, lighting and composition. This is where image-generating AI enters the methodological frame.

Navigating Policies of Visible Nudity

Following this challenge, my methodological development prioritised identifying a tool that would be digital, accessible, and user-friendly, enabling a collaborative visual practice. As I was looking for a digital tool which would make it possible to co-create visual material such as collages or image editing within digital interview settings, I initially came across Canva, a free web-based platform. While roving around the application’s interface, it suggested to try out its AI function. Yet, on a few test prompts not only including the explicit term “nude” but also descriptions like “without clothes” or “topless bikini”, the platform responded with no images but the notification that the images generated may not adhere to the application’s guidelines.

This prohibition was explained with reference to the platform’s ethical guidelines and their call to “be a good human” (Canva, n. d.) as seen in the screenshot. The way Canva’s policies equate nudity with obscenity mirrors what Cover (2003) argues is a “backlash against ‘sexuality’ and not nudity” (ibid. 67). Within his argument, contemporary Euro-American culture is marked by an increased saturation of sexuality across media and public discourse and at the same time boundaries that police where and how nudity may appear are reinforced (ibid.). This paradox already reveals that it is not nudity itself that is framed as inherently problematic. Rather, in that the sexual and the non-sexual increasingly collapse within nudity, it becomes a thread to regimes of the gaze (ibid. 60–61). In this light, the prohibition of AI-generated nudes can be seen less as a neutral safety measure and more as a reflection of dynamics between visibility, desire, and control. Similar dynamics appeared once more during my research phase, adding another facet to policies of visual nudity and digital tools.

Looking for a tool that allowed depictions of nudity, I turned to BasedLabs, a web-based AI image-generation platform combining different AI tools. However, as my research evolved, BasedLabs revised its policy, and the Nude AI Generator got deleted. This shift was tied to its use of Stable Diffusion, trained on the LAION-5B dataset – a dataset that came under scrutiny when researchers discovered it contained child exploitative material (e.g. Grüner, 2023). In response, parts of the dataset were removed, and filtering systems were implemented (see Thiel, 2024).

This controversy puts another spotlight on how AI infrastructures are increasingly entangled with visual ethics and specifically the legality of visual material. In his observation of how nudity and sexuality increasingly converge, Cover (2003) highlights the particular role of images depicting naked children. He emphasises that the boundary between legitimate representations and child pornography depends primarily on interpretation rather than on production context. This is of special interest for the case of image-generating AI like Stable Diffusion since the download or storage of such material is not only an ethical question but simply illegal in most legal systems. The regulation in accordance with legal frameworks hence also serves to protect users from legal consequences if the generated content unintentionally is interpretable as child pornography.

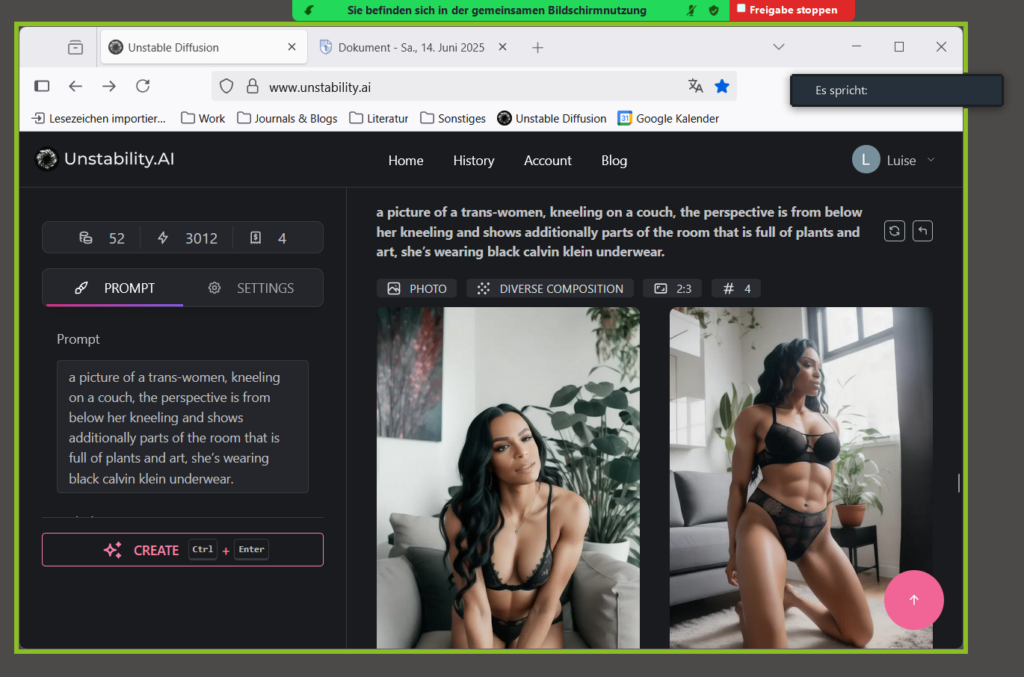

With BasedLabs adjusting its legal framework, I once again found myself searching for a digital tool suited to exploring the aesthetic and visual dimensions of queer nudes. Eventually, I came across Unstable Diffusion. On its landing page the platform promotes creativity without limits, as shown in the screenshot. Simultaneously, “[g]enerating Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) or any pornographic content depicting characters who appear to be or are identified as 18 years old or younger is absolutely prohibited” (Unstable Diffusion, n. d.), a closer look at the user guidelines reveals. Yet, this restriction governs content creation in both directions – limiting intentional input as well as possible unintentional output –, as the platform actively declines to produce images suspected of breaching its policies (ibid.).

While this platform technically allowed for the creation of queer nude representations, it pointed towards ethical and practical concerns that pertain to the most web-based platforms: The requirement of an account, which would mean to expect participants to hand over personal data to third-party providers by asking them to use the platform themselves. Accordingly, to navigate ethical and technical constraints, I set up a digital workaround that maintained both participant anonymity and collaborative engagement.

Photo-Elicitation with Image Generating AI in Practice

Using my university’s Zoom license, I shared my screen in real time to generate images with Unstable Diffusion AI jointly, as the screenshot illustrates. In these settings, participants and I simultaneously co-wrote image prompts in a shared text document. This approach supported anonymity and critical engagement with visual material as well as safeguarding participants’ privacy.

This method proved effective in enabling participants to engage actively, creatively, and reflectively with visual aspects of nudes. As one participant perceived, my role as both guide and co-prompt creator helped them feel more at ease and involved. In this sense, the setup facilitated a co-creative and collaborative process, allowing engagement without the discomfort of feeling directly observed. The shared screen, live co-writing of prompts, and real-time image generation created a space of mutual participation. This aligns with Palmberger and Budka’s (2020) argument that digital tools can meaningfully extend collaborative ethnographic methods online.

Building on the collaborative image-making process, each session ended with a discussion reflecting not only on the images but also on the infrastructures behind the image generation. For example, the model often refused to translate visually what was described as “androgynous”, “masculine” or “feminine” “features”. These absences sparked deeper conversations about how language mediates between queer self-description, bodily representation, and AI’s capacities. For example, one collaborator observed that these omissions highlight the entanglement between images and the metadata within the training data shaping the visual output.

This reflexive dimension further mirrors what Palmberger and Budka (2020) see as a core strength of ethnography in the digital age more generally: the ability to explore both “mediated personal relationships […] [and] the socio-technical entanglements between humans and technologies” (Palmberger and Budka, 2020, emphasis by the author). By reflecting on what the AI could and could not render, participants and researcher became increasingly aware of the infrastructural interplay of text and image, but also of how context influences both. At the same time, these reflections resonate with Schaffer’s (2008) call for a more nuanced approach to (in)visibility. As she cautions to equate visibility with empowerment, she advocates for a “reflexive representation practice (both in perception and depiction) that insists on its situatedness, contingency, and provisionality” (ibid. 51, translated by the author). In this sense, collaborative image generation with AI created a space attentive to the ambivalences of queer visibility, fostering situated knowledge production conscientious of the constraints and possibilities of digital representation.

References

- Albury, K., & Crawford, K. (2012). Sexting, Consent and Young People’s Ethics: Beyond Megan’s Story. Continuum, 26(3), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2012.665840

- Canva (n. d.). AI Safety at Canva. Canva. https://www.canva.com/policies/ai-safety/

- Cover, R. (2003). The Naked Subject: Nudity, Context and Sexualization in Contemporary Culture. Body & Society, 9(3), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X030093004

- Fawns, T. (2021). The Photo-Elicitation Interview as a Multimodal Site for Reflexivity. In P. Reavey (Ed.), A Handbook of Visual Methods in Psychology: Using and Interpreting Images in Qualitative research (pp. 487–501). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351032063-3328

- Grüner, S. (2023, December 21). Größter KI-Datensatz enthält Bilder von Kindesmissbrauch [Online Magazin]. Golem. https://www.golem.de/news/stable-diffusion-groesster-ki-datensatz-enthaelt-bilder-von-kindesmissbrauch-2312-180555.html

- Harper, D. (2002). Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345

- Palmberger, M., & Budka, P. (2020, November 13). Collaborative Ethnography in the Digital Age: Towards a New Methodological Framework. Digital Ethnography Initiative. https://digitalethnography.at/collaborative-ethnography-in-the-digital-age-towards-a-new-methodological-framework/

- Unstable Diffusion. (n. d.) Guidelines. Unstable Diffusion. https://www.unstability.ai/guidelines

- Schaffer, J. (2008). Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit: Über die visuellen Strukturen der Anerkennung. transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839409930

- Thiel, D. (2023). Identifying and Eliminating CSAM in Generative ML Training Data and Models. Stanford Internet Observatory. https://doi.org/10.25740/kh752sm9123

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my research partners for their trust and for diving with me into the complexities of queer nudes. I am also grateful to Philipp Budka, Monika Palmberger, and Suzana Jovicic for their thoughtful feedback and for the opportunity to publish this blog post. Lastly, albeit unconventionally, I acknowledge the support of ChatGPT, dict.cc, and Quillbot for helping me to navigate the nuances of language in a grammatically coherent way.

*Luise Erbentraut is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Media and Communication at the University of Hamburg and member of the Digital Anthropology Lab at the University of Tübingen. With a background in social and cultural anthropology and philosophy, their research combines digital ethnography with feminist and queer theory. Their PhD project “Felt Cute, Sent Nude: Queer Visual Literacies of Desire’s Affective Arrangements of Digitized Bodies,” explores nudes as a queer, cultural practice of everyday life.