Sanderien Verstappen*

Report on the RAI conference panel “Critical play: Smartphones as a mode of creative engagement with crisis” during the RAI Film Festival 2021.

Smartphones are increasingly used in anthropological research, teaching, and knowledge dissemination. While their usage is not limited to the pandemic, situations of social distancing and online teaching have increased the dependency on digital media and triggered new engagement with the smartphone’s potential. Some of these endeavours in smartphone-based anthropology were discussed during the panel “Critical play: Smartphones as a mode of creative engagement with crisis” on March 25, 2021, during the online visual anthropology conference at the film festival of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI). The panel was convened by Mark Westmoreland (Leiden University) and me (University of Vienna), with participation of Laura Haapio-Kirk (University College London, UCL), Kana Ohashi (Tokyo Keizai University) and Daijiro Mizuno (Kyoto Institute of Technology). In this blog post I summarize some of the main points from the panel discussion, focusing on one theme of shared interest: the use of the smartphone for the dissemination of anthropological research findings.

How can the smartphone be used for public engagement and knowledge exchange in anthropology? Laura Haapio-Kirk has gained much experience in this field. As a public engagement officer for the RAI and for Daniel Miller’s research project Why We Post, she has supported many anthropologists in disseminating their research findings in non-traditional ways, especially on social media. For a RAI project, for example, she invited anthropologists to share findings through drawings and graphics, which resulted in the digital exhibition Illustrating Anthropology with a parallel Instagram feed. In her presentation, Laura highlighted the importance of visual communication in public outreach activities, for example, social media posts with an appealing image are clicked on much more frequently than purely textual ones. Her own PhD research is embedded in Miller’s Anthropology of Smartphones and Smart Ageing project, in which she investigates the smartphone practices of elderly people in Japan. Her growing knowledge about their media usage enables her to also develop forms of knowledge dissemination that make sense to the participants – for example, an illustrated book that will be designed to maximize accessibility and readability on a smartphone.

Another mode of smartphone-based anthropology was discussed by Kana Ohashi. Kana spoke also on behalf of her collaborator Daijiro Mizuno, who could not personally participate in the live discussion. Daijiro Mizuno is a single father, whose wife Mie died of stomach cancer a couple of years ago, three months after their son’s first birthday. With cancer being the most common cause of death in Japan and very little knowledge available about the impact of cancer on family life, Kana and Daijiro decided to capture the rapid changes in Daijiro family from the moment of Mie’s diagnosis. Kana, a visual ethnographer, had initially planned to follow the process with a film camera. However, to avoid exhausting Mie’s time and strength, she decided to shift to the more flexible medium of the smartphone. From then on, Daijiro made his own video and photo recordings, saved these on a Google Drive, and had weekly online sessions with Kana to discuss the footage. They used the footage to create a 20-minute documentary film, Transition (2019), which was screened at the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam. The project shows how a smartphone can be used to conduct collaborative research in a private sphere with people undergoing rapid or difficult life transitions in crisis situations. Moreover, such a smartphone-based collaborative project can result in a high-quality documentary film.

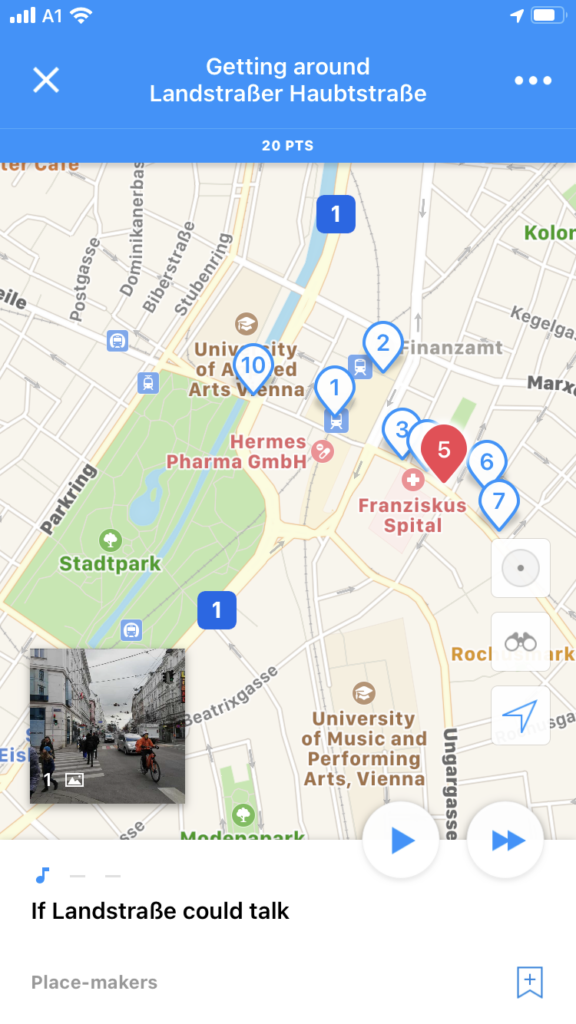

My presentation introduced the form of the smartphone-based audio walk as a tool of pedagogical and public knowledge sharing in the anthropology of space and mobility. Social researchers with spatial questions have shown keen interest in mobile devices that generate locational information, either to track human movements as behavioural data or to develop participatory modes of researching and representing space. Audio tours use the locational technology of the smartphone not to gather data, but to communicate about research findings in a public space. They do this by linking audio narratives to spaces on an interactive map, so that smartphone users can click on them in the exact space where the researcher wants them to be listened to. I developed this form with my students during a course in the Anthropology of Space (2020-2021) at the University of Vienna. I had been inspired by the audio walk Wadlopen in Nimma by the radio makers Jozien Wijkhuijs and Dennis Gaens, which I had listened to in the summer of 2020. Their audio walk communicates natural science knowledge about climate change in a provocative way, using 3D microphones and a fictional plot that invites the listener to imagine a future of rising seas and stormy weather while strolling along the river Waal in the Dutch Ooijpolder. After a chat with the makers, I was able to modify and simplify the form so that I could implement it in my teaching. My students conducted research on one joint research location in Vienna (the Landstraßer Hauptstraße), used their own smartphones to record audio, and used open access Audacity software to edit these into audio narratives. During the last class, we met on the research location to walk the audio tour we created together. At a time when on-campus teaching was forbidden due to Corona, the walk offered our group a unique moment of learning together on-site in an open-air space, while our smartphones enabled us to maintain social distance regulations. The audio walk is publicly available on the smartphone app izi.Travel (Getting around Landstraßer Hauptstraße).

The presentations were linked to broader discussions in multimodal anthropology by Mark Westmoreland. Mark highlighted the everyday usage of the smartphone, the multiplicity and ubiquity of its use, as well as its sensory dimensions. He himself started using the smartphone as an experimental pedagogical tool when he was a university lecturer at the American University in Cairo. During the Arab Spring, his students made film recordings with their smartphones to reflect on what was happening on the streets. Nowadays, he develops smartphone-based pedagogies at the University of Leiden. Reflecting on the evolving use of the smartphone as shown in the various panel presentations, Mark invited further analysis of the corporeal and affective aspects of the smartphone experience, which interlink with the networked aspects.

Given the diversity of approaches in the presentations, the panel showed that smartphones have become entangled with anthropological practices in a multitude of ways, highlighting the inherently multimodal character of contemporary anthropology. Critical questions raised during the discussion concerned the inequal access to smartphones, the commercial character of most digital infrastructures, and public concerns over data tracking and privacy. These questions trigger further thought about the conditions under which these new opportunities for knowledge exchange are being developed.

Preferred citation: Verstappen, S. (2021, April 2). Smartphones and public anthropology. Digital Ethnography Initiative Blog. https://digitalethnography.at/2021/04/02/smartphones-and-public-anthropology/

* Sanderien Verstappen is assistant professor with tenure track in Social and Cultural Anthropology with a focus on Visual Anthropology at the University of Vienna, and director of the Vienna Visual Anthropology Lab. She has published articles and made films on topics of migration, mobility, and development, and develops multimodal media practices in research and teaching.

One thought on “Smartphones and Public Anthropology”

the very helpful article it helps me a lot, information is very effective for me!!