Ioana-Sophia Cîrlan*

This blog post is a revision of a text written for the seminar “Digital Identities and Socialities” by Philipp Budka for the MA program “CREOLE – Cultural Differences and Transnational Processes” at the University of Vienna.

The power of social media to shape electoral campaigns, amplify outsider candidates, and mobilise new publics has become increasingly evident, and the recent Romanian presidential elections illustrate this particularly clearly. Allegations of foreign interference and irregular digital promotion supporting a political outsider led the Romanian Constitutional Court to cancel the results of November 2024 and order a complete do-over in May the following year.

In this highly tensed and polarised atmosphere, I turned my attention to social media as a site where everyday digital interactions are points of departure for political meaning-making. When candidates are in constant contact with their supporters through likes, comments, and shares, political campaigns become arenas where identity is constructed relationally (Alcoff, 2003). The politician and the people come together in new forms of digital socialites (Bareither et. al, 2023), bounded by political alignment, pride, fears, expectations, a sense of belonging and understandings of the “truth”.

Who is George Simion?

George Simion is the leader of the populist far-right party Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), who ran for president both in 2024 and 2025; however, with very different results. While in May 2025, he was the runner-up, garnering over 40% of the votes cast in the first round, just six months earlier, in the November elections, he ranked fourth with only 13%.

His initial loss was explained largely through the unexpected rise of independent candidate Călin Georgescu, a previously marginal figure who quickly attracted a substantial online following (Ross et al., 2024). Georgescu’s exclusion from the repeat election in 2025 after the Constitutional Court invalidated the first round reshaped the field. Many of his supporters redirected their attention to Simion, who actively positioned himself as Georgescu’s successor.

A New Style of Political Visibility

While the use of social media for political purposes is not particular to the Romanian election landscape or to Simion, what encouraged me to investigate the 2025 elections was how Simion seemingly incorporated his supporters’ efforts in campaigning. I was able to study these dynamics through digital ethnography, recognising online engagement as part of everyday social life (Boellstorff, 2008; Miller & Horst, 2012).

Working with case studies (Yin, 2013), I examined George Simion’s online campaign between April and May 2025 and selected three key campaign materials as analytical anchors. Then, I sampled users’ responses online, referring to comments, captions, reposts, shares, supporters’ groups, filters, songs, and other platform-specific tools, laying the ground for thematic analysis (Stevens & Dusi, 2023). In dealing with supporters’ materials, I anonymised the content, avoided reproducing identifiable personal data, and used screenshots only from public campaign materials to ensure ethical handling of online posts.

The chosen methodology reflects Simion’s strategy. As he abandoned traditional campaign practices, withdrawing almost entirely from public appearances, debates or interviews, his social media became the primary channel where he kept in contact with his supporters. Thus, I aim to show how this campaign became a space where Simion and his voters co-authored a political identity online (Alcoff, 2003), bound in the same digital collective (Bareither et al., 2023).

From Georgescu to Simion

Simion framed himself as the legitimate successor to Călin Georgescu, refusing to announce his re-run before Georgescu’s was officially banned. The passing of the torch came at the Easter Mass when the two were strategically photographed together. The picture quickly spread across the Internet (Postill, 2012), with voters interpreting it as a sign of clear endorsement. Simion kept Georgescu at the centre of his messaging, promising a “return” of the banned politician either as president, prime minister, advisor or something he called the “highest position in the state”.

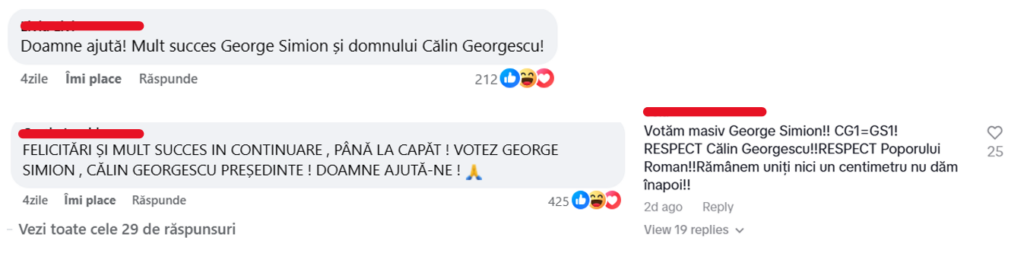

Even though Simion never explained how such vague and seemingly contradictory promises would materialise, his supporters embraced this rhetoric. As seen in the comments under Simion’s post (Figure 2), online users expressed enthusiasm for this promise, writing “Călin Georgescu President, George Simion Prime Minister” or other similar phrases. The shadow of Georgescu weighed on Simion’s campaign, as some users saw Simion as just a temporary fix until the “rightful” (e.g., Georgescu) politician could be reinstated.

The Election as a Battlefield

The first electoral material Simion posted on his social media page was a 2-minute video. As illustrated in Figure 3, Simion is filmed walking towards the camera, surrounded by his wife and his inner circle, while in the background a famous Romanian military song plays. Simion explains how his campaign is “fight for respect”, underlying the idea that his run for the presidency is more than a political act.

Shortly, the ”fight” began circulating among online supporters. Under the label “Simion’s soldiers” (“#soldatsimionist”), some users took to social media to support the candidate’s “fight”, embedded in a sense of urgency: “Ne cheamă și frații, nu la o campanie ci la o misiune istorică” (trad. “Our brothers are calling us not to a [political] campaign but to a historical mission”).

References to “fighting” persisted among Simion’s supporters until the end of the campaign. After losing, he briefly refused to concede, which some supporters read as a betrayal. In response, they recirculated “fight” themed posts and shared comments hinting at mobilisation in various online spaces. Simion later explained his hesitation as an attempt to avoid “bloodshed” (Benea, 2025). The combative framing originated with Simion, but it was his supporters who gave it more literal and militant interpretations.

Conspiracy and Transnationalism

To make the fight worth fighting, Simion had a good reason to create an enemy, frame opposition as corrupt or illegitimate tactic typically carried out by populists (Motiff, 2016; Pasieka, 2017, 2019). Simion constructed an easy-to-follow us-them narrative, where he and his supporters were against the “globalist” or “sorosit” elite (label implying someone is influenced by George Soros, often used to delegitimise NGOs, journalists, or political opponents), spreading conspiracy theories, evaluated through affective cues and shared emotions (Bareither et. al, 2023).

The constant atmosphere of distrust in the state authorities led supporters of Simion to write online

“MAI, sistemul corrupt si inefficient, va cadea, votam masiv” (trad. “MAI [Ministry of Interior] the corrupt and inefficient system, will fall, we vote massively”) or frame the final election results as illegitimate, both before and after the vote. An example of supporters’ distrust is that, particularly in the diaspora, they organised ad-hoc protests in front of polling stations.

When I voted at the Romanian Embassy in Vienna, I witnessed one such demonstration. While I can’t claim direct causality between online content and these protests without long-term engagement with the group, the recurrence of similar motifs in both spaces suggests a possible influence of digital campaigning on street action (Miller & Horst, 2012).

Labels that Stick

One of Simion’s most effective strategies to unify his supporters around a shared language was the derogatory nickname he gave his opponent, “mucusor”, an ironic play on the name Nicușor Dan. The insulting title, which gained traction online, intended to portray the competitor as careless and socially awkward, someone who failed to follow basic etiquette, allegedly sticking his fingers in his nose.

The nickname plays on the Romanian word “muc” (trad. “snot”), giving it a demeaning edge. Its widespread use among online users across social media platforms shows how it became a recurring reference point in discussions about the opponent, subtly shaping how he was perceived as a leader. Here, “mucusor” is similar to Trump’s “sleepy Joe”, “crooked Joe” or “crazy Hillary” and “lying Hillary”.

DIY Campaign Content

As I have already shown, Simion’s supporters are not passive observers but active participants in the political process. This agency extends beyond liking, sharing, or commenting on official content, as some grassroots initiatives, likely started by supporters, produced their own campaign materials.

To show their political preference, online users started their own video or image-based trends where they would post themselves with the message “I am not going to tell you who I am voting for, but there will be signs” while playing pro-Simion songs, such as “Adu caii Simione” (trad. “Bring the horses Simion”) and using visual hooks like Romanian flags, emojis, filters, etc. Interestingly enough, this witty trend caught so much visibility that it got appropriated and repacked by those who were supporting the other candidate in the race.

Final Reflections

Ultimately, George Simion lost the 2025 presidential election, despite reaching the runoff and mobilising a highly active online base. However, as far as I am concerned, Simion’s loss is precisely what makes this case illuminating. By recognising the agency of online users, through their engagement with official materials, responses, and creation of their own content, this study demonstrates the value of examining politics from the perspective of supporters.

While Simion lost the elections, he maintained an engaged base, highlighting that a campaign’s success can be measured in ways beyond just the vote count. In this case, digital ethnography helped me study how everyday online interactions become politically powerful.

At the time of writing, Simion remains a central figure in Romanian politics as the leader of the largest opposition party in Parliament, demonstrating that online mobilisation can sustain political relevance even in defeat.

References

- Alcoff, L. M. (2003). Introduction: Identities: Modern and postmodern. In L. M. Alcoff & E. Mendieta (Eds.), Identities: Race, class, gender and nationality (pp. 1–8). Blackwell.

- Bareither, C., Harder, A., & Eckhardt, D. (2023). Special issue: Digital Truth-Making: Anthropological perspectives on right-wing politics and social media in “Post-truth” societies. Ethnologia Europaea, 53(2). https://doi.org/10.16995/ee.9594

- Benea, I. (2025, May 21). Ce-a vrut să spună autorul? Am disecat cuvânt cu cuvânt discursul lui Simion. Experți: E instigare la violență. Europa Liberă România. https://romania.europalibera.org/a/analiza-discurs-simion-instigare-violenta/33420429.html

- Miller, D., & Horst, H. A. (2012). The Digital and the Human: A Prospectus for Digital Anthropology. In D. Miller & H. Horst (Eds.), Digital Anthopology (pp. 3–35). Berg. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003085201-2

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford University Press.

- Pasieka, A. (2017). Taking Far-Right claims seriously and literally: Anthropology and the study of Right-Wing Radicalism. Slavic Review, 76(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2017.154

- Pasieka, A. (2019). Anthropology of the far right: What if we like the ‘unlikeable’ others? Anthropology Today, 35(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12480

- Postill, J. (2012). Digital Politics and Political Engagement. In H. Horst & D. Miller (Eds.), Digital Anthropology (Vol. 1, pp. 165–184). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003085201-12

- Rezultate vot Alegeri prezidențiale 2024. (2024). Code for Romania. https://rezultatevot.ro/alegeri/prezidentiale-turul-1-2024/rezultate

- Rezultate vot Alegeri prezidențiale 2025. (2025). Code for Romania. https://www.rezultatevot.ro/alegeri/prezidentiale-turul-1-2025/rezultate

- Ross, T., Jack, V., & Petre, A. (2024, November 29). Who is Călin Georgescu, the far-right TikTok star leading the Romanian election race? POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/calin-georgescu-romania-elections-far-right-tiktok-nato-skeptic-russia-ukraine-exports/

- Stevens, P., & Dusi, D. (2023). Thematic Analysis: An Analytical Method in its Own Right. In P. Stevens (Ed.), Qualitative Data Analysis Key Approaches (pp. 293–314). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Yin, R. (2013). Case Study Research: Design and Methods: Applied Social Research Methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

*Ioana-Sophia Cîrlan is a master’s student in the CREOLE Program at the Department of Social-Cultural Anthropology, University of Vienna.